This summer, I plan to tackle Canada’s Great Divide Trail. I have already begun to jokingly preface all my post-hike plans with: “If I’m still alive…”

Professional projects? Assuming I’m still alive. Deferred hangouts and drinks in the fall? Contingent on my possession of a pulse.

I’m kidding, mostly. I certainly don’t plan to die on trail. But the disclaimer is a byproduct of the uncertainty I feel about the GDT.

After planning for so long, this hike is coming up quick, and in just under three months, it will all be over — the prep, the approach, and the hike itself. I will either have succeeded or failed by my own unforgiving standards. I’ll either be back in Berlin scheming up the next adventure or merging my decaying carbon with the rugged, exposed bones of the Canadian Rockies.

In fairness to myself, I’m not an inexperienced hiker. I solo thru-hiked the PCT in 2022 with nary a fall nor a serious overuse injury and successfully handled every quirk of weather, wildlife, and other hurdles that came my way.

So what am I even worried about?

Respecting the trail, recognizing the elevated level of difficulty and the real existence of things and situations that could kill me on it: That’s the first step towards mitigating the risks so that hopefully nothing will. You don’t want the epiphany of, “huh, this is actually a really serious environment” to strike for the first time when you’re already ass-deep in it with no plan.

The Things Likely To Kill You on Trail Are Almost Embarrassingly Mundane

I’m a firm believer that a little bit of pre-hike nerves can be a healthy thing: there are real dangers out there, whether to life and limb or your continuous footpath, and it’s best to be aware of them. But the fears that might come to mind for first-time hikers — large carnivores, human predators, etc. — aren’t the ones you should be focusing on. No, the deadliest parts of thru-hiking are less exciting on paper, but far more common and hazardous in real life.

When I mention the GDT to other hikers, they usually say something enthusiastic about the beauty, but then hedge any interest in doing it with wariness about the permit system and the grizzlies.

The permit logistics were certainly convoluted and I sure respect the bears, but they aren’t what I’m worried about. There’s not so much you really need to do about the bears. Buy the Ursack, learn to tie it, order a shoulder holster and some bear spray, practice deploying it, and hope you never have to use it. Keep your head and remember the behavioral best practices for de-escalating and peacefully enjoying a bear sighting. Hope for the best. Cool.

I’m honestly much more concerned about the weather.

Rain: Scarier Than Bears, Moose, and Mountain Lions

Hiking back into the Sierra over Kearsarge Pass in 2022, I was a bit worried by these clouds, but they turned out to be totally trivial. Weather in the Canadian Rockies: often decidedly less so.

The PCT can certainly throw curveballs, and heat is its own serious danger, but more often than not, it is at least a dry trail. (Cue folks incoming to mention the time they battled hypothermia in a PCT rainstorm, I’m sure. Exception! Not the rule!)

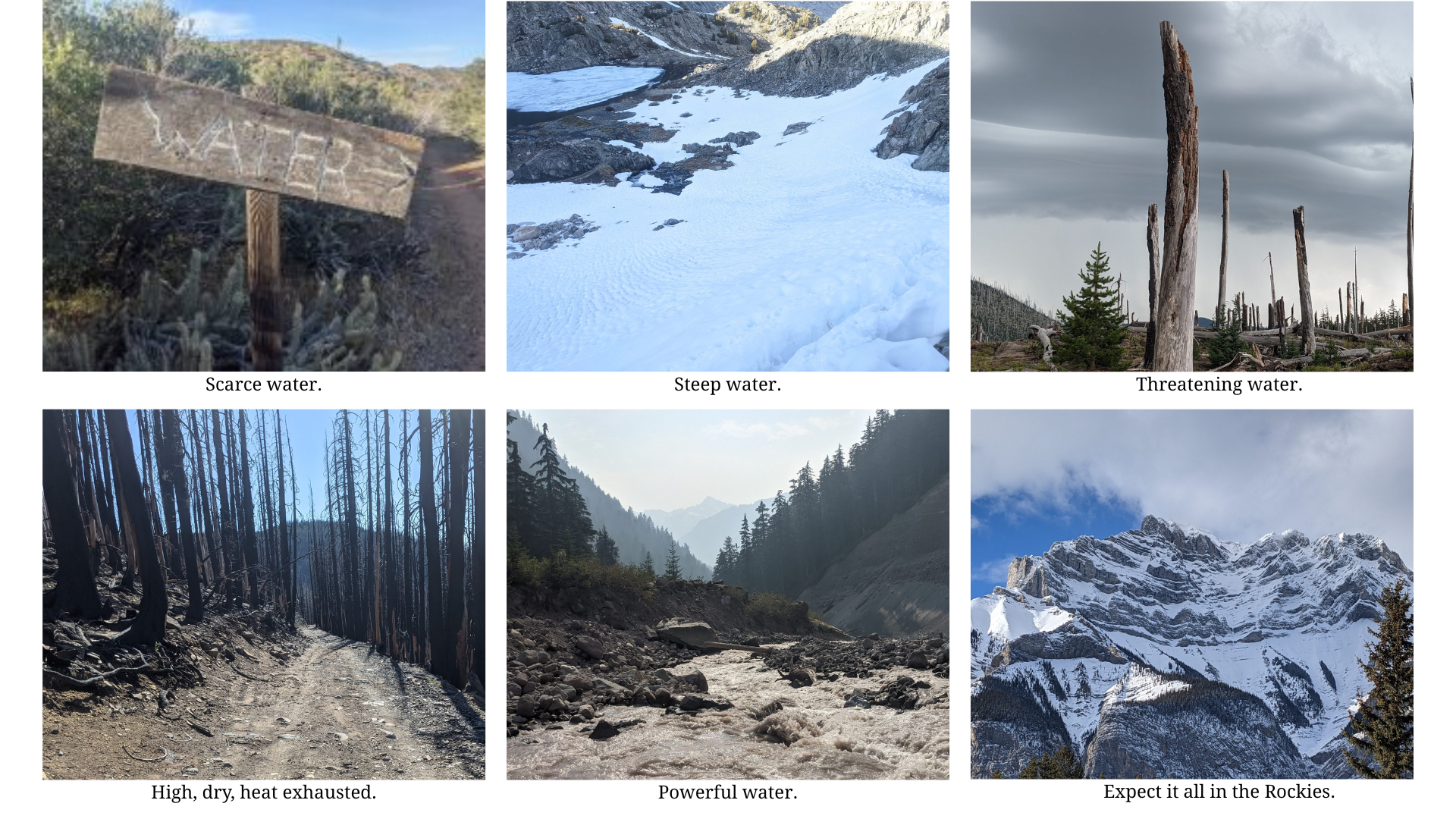

In the Rockies, on the other hand, absolutely any weather can show up, and it frequently does. Hammering heat on a dry ridge, summer snowstorms, lightning on high passes, wildfires, and the thing I’m most worried about: Days of sustained rain in a long section between resupplies. Not a passing cloudburst, but the kind of relentless precipitation that seeps into every corner of your gear, steals the warmth from your bones, and threatens your ability to maintain your little island of mammalian homeostasis.

The threat of prolonged bad weather brings with it a thousand choices. You could trade your lightweight standard thru-hiking kit for other gear, but there’s weight to consider, and cost.

That pricey DCF palace — is it still stormworthy after 3000 miles? Was it ever? Are those pinholes in the roof? Let’s order some more repair tape.

How about that eye-wateringly expensive down sleeping bag—could you keep it dry enough, and yourself alive, if it rained through all of the final remote sections? A planned ten days from Jasper to the terminus and another couple days on the exit?

What about the risk of trenchfoot if it’s constantly raining, on top of the braided river crossings? Best order some special salve.

How about my rain jacket? Have I bought one that’s good enough?

My hands — should I get high-end ultralight shell mitts, or emulate the locals who swear by dish gloves over liners? I’ll definitely have my usual emergency handwarmers in the kit—but one pair? Two? More? Don’t pack your fears. No, maybe do, this time. If the down sleeping bag gets soaked, the handwarmers could save your life. And so on.

Cougars Hate Banjo Music

Your author, blissfully pitching her tent on a territorial mountain lion’s turf.

On the PCT, a mountain lion once circled my tent in the middle of the night. Camped alone, I woke to the almost silent impact of its paws on the earth, just on the other side of my dragonfly-wing tent wall. I drifted groggily in and out of sleep, not sure what sort of creature I was hearing, until it began to snarl, chirp, and make other telltale cougar vocalizations.

There is a detached, competent persona that lives at a level removed in my brain, like a coach who calmly gives me orders or encouragement when my life might be in danger: whether navigating sketchy, exposed terrain and water crossings, or when a random unhinged-looking dude materializes out of the bushes on one of my urban night runs and starts following me.

At that point during the cougar encounter, the “coach” nudged the rest of my sleepy brain firmly and insisted: You need to wake up and do something about this.

So I did. I sat up, turned my headlamp and phone light on, picked a nice energetic Mumford & Sons track, and blasted it at full volume. I think I sang along, waved my light-wielding arms enthusiastically around the tent, and generally attempted to give the impression of a great number of loud alien beings inside this uncomfortable foreign object. The old banging-on-pots-and-pans trick, for the ultralight modern age.

When the track ended, I listened to the night. No cougar. Problem solved, thank you Mr. Mumford. I went back to sleep.

A millennial will live-tweet her own demise, or would have, pre-X. No service on the GDT, though.

When I tell that story, people often look aghast. For many, an encounter with a predator is the ultimate fear evoked by the idea of adventuring in the backcountry.

But while I took the situation seriously, in the moment, I was not actually terrified. I needed to do something to deter the curious, territorial cat, and I did, and it was pretty low-effort. While it could have escalated, as long as the animal did not attack, I was physically fine.

It’s often like that with wildlife encounters. The vast majority of bear sightings remain non-confrontational and don’t actually require you to do anything.

No, the truth is, the really terrifying moments on a hike are when some small upset to your ideal living conditions threatens homeostasis.

Homeowhat?

Staying Alive: It’s All About Homeostasis

Basically, your body and its organs only keep functioning within a narrow band of physical conditions. The right gear can expand that band somewhat, but not indefinitely. When the environment deviates too much from the ideal conditions for human life, your organs can work harder to compensate for a while. Hopefully you manage to rescue yourself during that window. If not, in an often surprisingly short period of time, you will die.

If you look at some statistics on known thru-hiker deaths on long trails, the vast majority are not from these projected fears expressed by the uninitiated. There aren’t a lot of fatal predator attacks and murders — not zero (wtf, AT) — but not many.

Most deaths are from falls in steep terrain, being hit by rock or deadfall, drowning in water crossings, heat exposure, and hypothermia. Folks also get hospitalized with hyponatremia — not enough salts — and rhabdomyolysis, the bugbear of FKTers and other elite athletes, which can be brought on by intense exertion and dehydration.

Altitude sickness is also a problem of homeostasis, in which factors like reduced oxygen and potential dehydration conspire to make your organs struggle, sometimes to fatal effect.

Thriving atop Whitney, thanks to Imodium and electrolytes.

Don’t Forget the Electrolytes

The stats track with my own anecdotal experiences on the PCT. In the desert, I helped a couple hikers struggling from dehydration and heat exhaustion, due to electrolyte imbalance and neglecting to actually consume the water they were carrying.

Descending Mount Whitney, I found a hiker collapsed from altitude sickness and slowly shepherded him to a lower elevation, again while sharing electrolytes and reminding him to actually drink.

Entering the Sierra from Kennedy Meadows South, I had experienced a brief altitude scare myself when I got above 10,000 feet and my gut suddenly revolted. I mean, four catholes in the space of an afternoon. I would nip off trail, go through my whole routine, clean up, attempt to rehydrate, slowly hike on, and before long, my gut would once again reject the fluid and fuel I was trying to cautiously introduce.

After the fourth stop, I leaned against a boulder and felt a cold, sober awareness creep over me. I contemplated both the flippant and the gravely serious aspects of my predicament.

Even my well-equipped and hygiene-conscious toilet kit of TP, copious wet wipes, ziplocs and disposable gloves is not stocked for a week in the Sierra if this frequency of dumps continues, and damn it, this would be a stupid reason to skip Whitney; enough food but not enough TP.

And:

… If I can’t keep fluids in, I will deteriorate very fast up here. I have to fix it.

Fortunately, an Imodium tablet and a cautious sip of water with added lemon Liquid IV electrolytes broke the cycle of doom. Froze my digestive system for about a day, which was long enough to acclimate to the exertion at higher altitude, and the citrus electrolytes were kind to my system as I slowly rehydrated.

In reality, I think I was in more immediate danger at that moment than while being circled by a curious wildcat. Yet when you tell people you’re going adventuring in the mountains, nobody gets big eyes and asks about your strategies for avoiding gut issues and maintaining general homeostasis.

They should, though. We are mostly water, and one way or another, it’s almost always water that wrecks your shit — its presence or absence.

Too much water falling from the sky. Slipping on frozen water on the ground. Too much meltwater in the river. Not enough water in your body. Enough water in your body, but not enough salts. Water in your body contaminated by pathogens. Managing the water in and around you is the lion’s share of the business of not dying out there.

The Fear of Failure: Have I Trained Enough?

My biggest fears on the trail pretty much boil down to the fear of personal failure, which encompasses death by hypothermia and other weather issues, drowning in rivers, and also being forced off trail by the kind of injury so incapacitating that no amount of grit, endured agony and abused ibuprofen would allow me to move through it.

Since I am a cautious, controlled hiker in my movements and swear by the motto “all terrain is no-fall terrain,” I’m probably more likely to experience an overuse injury than a traumatic one — a theory also borne out by the statistics on why people don’t finish their hikes.

The nemesis of the long-distance hiker: Catastrophic tendonitis, the kind that doesn’t just hurt, but damages the tendon to the point that it cannot support your full range of motion.

I had that once, as a cross-country runner in high school. It took me out of commission for half a season and sent me to physical therapy for two months, rebuilding the ability to bounce while standing on one foot. That memory lurked in my mind at age 30 when preparing for the PCT. If I was going to quit my job, give up my housing, dismantle my life, and spend a ton of money on this dream, I would not see it shattered by a finicky tendon.

To that end, over two years and three months of training (mostly urban, with a few alpine shakedown trips), I obsessively logged twice the distance of the PCT itself. 5300 combined miles of running or walking with a loaded pack. Boring and probably overkill, but it served its purpose: When I showed up at the Mexican border, everything from the hips down was bombproof.

This time around, I have trained, well, not to that extent.

I’m not building the long-distance hiking machine from scratch like I was then, but I still worry. I hope that I’ve done enough, maintained enough. Or at least that if pain should surface, it’s the kind I can push through for 700 rugged miles.

I knew I probably couldn’t just outrun an injury on the PCT; the trail is long enough that any damage tends to build. I knew mentally and physically strong hikers who were finally taken out by tendonitis even after making it through most of California.

Sometimes it’s the luck of the draw, whether a damaged tendon is one you can force into line, or whether lost functionality turns not just painful, but non-negotiably hike-ending.

The fear of overuse injury will stay with me until I hopefully reach a point where I know I have this thing in the bag. Until then, I’ll try to keep building the body with strength training and volume, and be religious about evening stretches with cork ball and PT band on the hike itself.

Be Afraid and Do It Anyway

“Quit using the trail as therapy,” I hear you say. “All this getting in your head and building up unhealthy ideas around failure and success — are you actually afraid of the rain, or just of what it would mean for your sense of self-worth if you failed by your own manufactured standard?”

Friends, come on, leave me my unhealthy coping mechanisms for now — can’t be stealing all my inner growth from the future!

At any rate, there’s something to be said for having a difficult goal and not forgiving yourself all possible outcomes in advance. Sometimes the magic happens in that space of wanting and fearing, stressing and striving. Maybe I just have to suffer a little to feel alive. When the shiver of fear creeps into my spine, it means I’m here on this earth, in my animal self, deliciously embodied.

I think many habitual thru-hikers share that trait, whether innate or chemically reprogrammed into us after months of high endorphin levels: The fear and the challenge are more of a magnet than a deterrent. We note our fears, we try to mitigate risks and make good decisions, but we don’t turn away from a bit of Type II fun.

That thrill of uncertainty, heading into the unknown, success not guaranteed: That’s how I know it’s worth doing. Facing the thing that both attracts me and makes me uncomfortable, and hopefully thriving within that discomfort, and getting stronger, and living to tell the tale.

Let’s hope!

Featured image: Photo via Caitlin Hardee. Graphic design by Chris Helm.