Last fall, the country singer Parker McCollum played a gig on the south shore of Lake Tahoe — the final date of a lengthy tour behind 2023’s “Never Enough” — then flew directly to New York City to start work on his next album.

“Probably the worst idea,” he says now, looking back at his unrelenting schedule. “I was absolutely cooked when I got there.”

Yet the self-titled LP he ended up making over six days at New York’s storied Power Station studio is almost certainly his best: a set of soulful, slightly scruffy roots-music tunes that hearkens back — after a few years in the polished Nashville hit machine — to McCollum’s days as a Texas-born songwriter aspiring to the creative heights of greats such as Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell and Townes Van Zandt. Produced by Eric Masse and Frank Liddell — the latter known for his work with Miranda Lambert and his wife, Lee Ann Womack — “Parker McCollum” complements moving originals like “Big Sky” (about a lonely guy “born to lose”) and “Sunny Days” (about the irretrievability of the past) with a tender cover of Danny O’Keefe’s “Good Time Charlie’s Got The Blues” and a newly recorded rendition of McCollum’s song “Permanent Headphones,” which he wrote when he was all of 15.

“Parker’s a marketing person’s dream,” Liddell says, referring to the 33-year-old’s rodeo-hero looks. “And what happens in those situations is they usually become more of a marketed product. But I think underneath, he felt he had more to say — to basically confess, ‘This is who I am.’” Liddell laughs. “I tried to talk him out of it.”

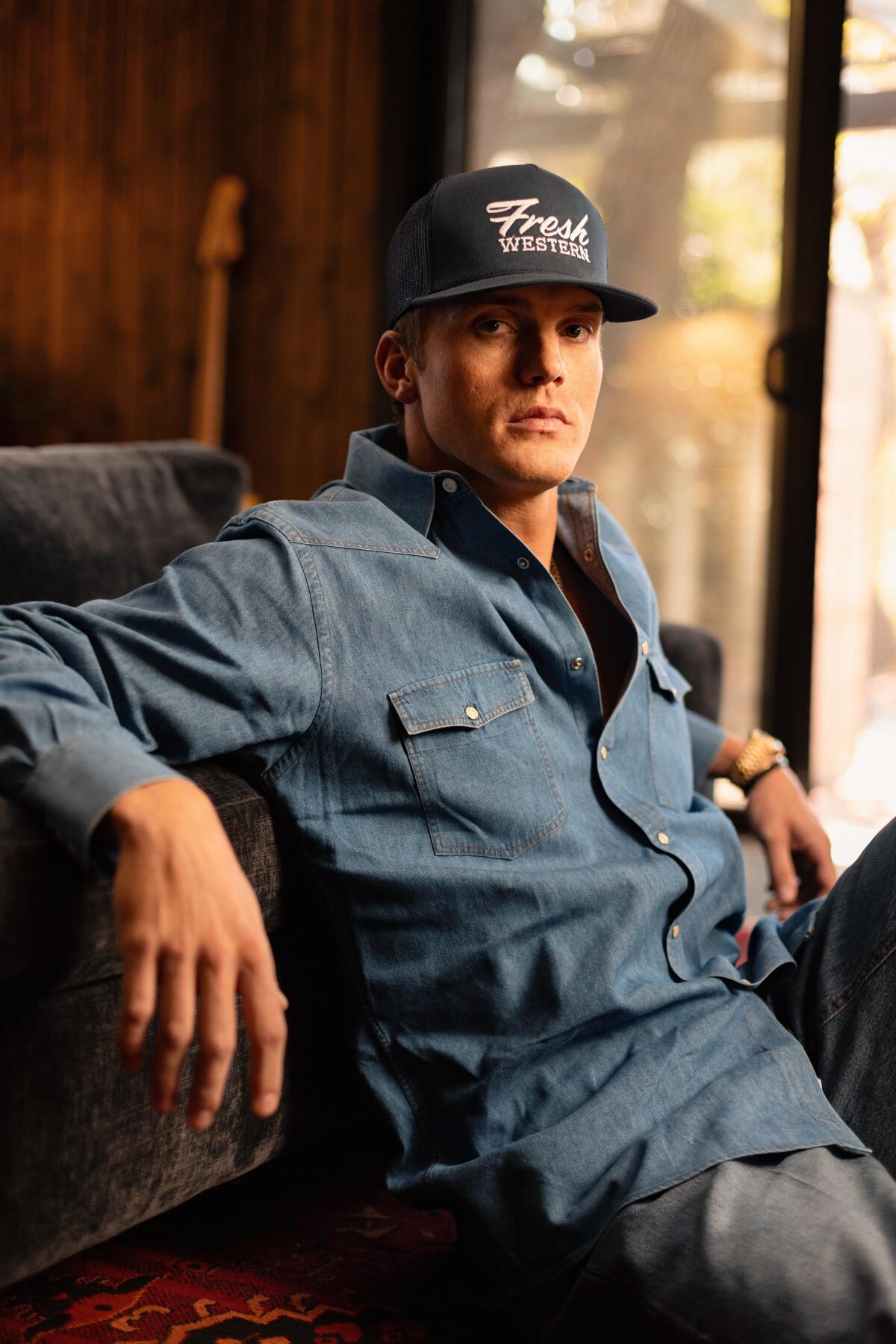

McCollum, who grew up in privileged circumstances near Houston and who’s now married with a 10-month-old son named Major, discussed the album on a recent swing through Los Angeles. He wore a fresh pair of jeans and a crisp denim shirt and fiddled with a ZYN canister as we spoke.

I was looking online at your —

Nudes?

At your Instagram. The other day you posted a picture of a box of Uncrustables on a private jet.

That photo was not supposed to make the internet. That was an accident — my fault. I don’t ever post about my plane on the internet.

You’re a grown man. Why Uncrustables?

That’s an adult meal that children are very, very fortunate to get to experience.

Did you know when you finished this record that you’d done something good?

Yes. But I didn’t know that until the last day we were in the studio and we listened to everything, top to bottom. The six days in the studio that we recorded this record, I was s—ing myself: “What the f— have I done? Why did I come to New York and waste all this time and money? This is terrible.” Then on the last day we listened all the way through, and I was like, Finally.

Finally what?

I just felt like I never was as focused and convicted and bought-in as I was on this record. I felt kind of desperate — like, “Am I just gonna keep doing the same thing, or are we gonna go get uncomfortable?”

Why New York?

One reason is that city makes me feel like a rock star. In my head when I was in high school dreaming about being a songwriter or a country singer, I was picturing huge budgets, making badass albums in New York City or L.A., staying in dope hotels — just this fairy tale that you believe in. The other reason is that when you’re cutting records in Nashville, people are leaving at 5 to go pick up their kids, or the label’s stopping by and all this s—. I just wanted to avoid all of that — I didn’t want to record three songs on a Tuesday in June and then record three songs on a Tuesday in August. I wanted to go make a record.

Lot of history at Power Station: Chic, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie.

John Mayer wrote a song and recorded it in a day there — that song “In Repair,” with him and Charlie Hunter and Steve Jordan. That’s how I found out about the studio years ago. We actually ended up writing a song in the studio: “New York Is On Fire.”

A very John Mayer title.

I wanted to go in the late fall when the trees were changing colors and the air was cool.

Why was Frank Liddell the guy to produce?

I knew if he understood Chris Knight and the songs he had written that he could probably understand me and the songs I had written. I’d made half a record with Jon Randall, who’d produced my last two albums. And I love Jon Randall — he’s one of my closest friends in the world, four No. 1s together, multi-platinum this and multi-platinum that. But I just needed to dig deeper, and Frank was a guy who was down to let the songs do the work.

What do you think would’ve become of the record you were making with Randall?

It would’ve sounded great, and it would’ve had some success. But I don’t know if I would’ve been as emotionally involved as I was with Frank. Frank got a better version of me than Jon did.

What if nobody likes this record?

It’s like the first time I’m totally OK with that.

Country radio moves slowly, which means “What Kinda Man” may end up being a big hit. But it’s not a big hit yet.

It probably won’t be. The only reason that song went to radio is because “Burn It Down” had gone No. 1, and the label wanted another one. I was like, “Fine, go ahead.” I’ve never one time talked with them about what song should go to radio.

On this project.

Ever. I just don’t care. The song that goes to radio is very rarely the best song on the record.

What was the best song on “Never Enough”?

Probably “Too Tight This Time.” It’s slow and sad, which is my specialty.

You recently told Texas Monthly, “I don’t write fun songs. I’ve never really liked them.”

There’s some I like. “Always Be My Baby” by Mariah Carey f—ing slaps. I love feel-good songs. But in country music, feel-good songs are, like, beer-and-truck-and-Friday-night songs, and those have never done anything for me.

“What Kinda Man” is kind of fun.

But I think it’s still well-written. It’s not all the clichés that every song on the radio has in it.

What’s the best song on this album?

“Hope That I’m Enough” or “Solid Country Gold” or “My Worst Enemy” or “My Blue.”

Lot of choices.

I love this record. I don’t think I’ll ever do any better.

Is that a sad thought?

Eh. I don’t know how much longer I’m gonna do it anyways.

Why would you hang it up?

I don’t know that I’m going to. But I don’t think I’m gonna do this till I’m 70. We’ve been doing these stadium shows with George Strait — I think I’m out a lot sooner than him.

You watch Strait’s set?

Every night.

What have you learned from him?

When it comes to George, what I really pay attention to is everything off the stage. No scandals, so unbelievably humble and consistent and under the radar. The way he’s carried himself for 40 years — I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody else do it that well. I’d love to be the next George Strait off the stage.

I’m not sure his under-the-radar-ness is possible today.

I fight with my team all the time. They’re always trying to get my wife and kid in s—, and I’m like, “They’re not for sale.” I understand I have to be a little bit — it’s just the nature of the business. But at home, that’s the real deal — that ain’t for show.

“I can’t explain how deeply emotional songs make me — it controls my entire being,” McCollum says. “The right song in the right moment is everything to me.”

(Matt Seidel / For The Times)

I’d imagine People magazine would love to do a spread with you and your beautiful wife and your beautiful child.

They offered for the wedding. I was like, “Abso-f—ing-lutely not.” I don’t want anybody to know where I live or what I drive or what I do in my spare time. And nowadays that’s currency — people filming their entire lives. Call me the old man, but I’m trying to go the complete opposite direction of that.

One could argue that your resistance isn’t helpful for your career.

I’m fine with that.

Fine because you’re OK money-wise?

I’m sure that plays into it. But, man, my childhood is in a box in my mom’s attic. And nowadays everybody’s childhood is on the internet for the whole world to see. I’m just not down with that. I don’t want to make money off of showing everybody how great my life is. Because it is f—ing great. I feel like I could make $100 million a year if I was a YouTuber — it’s movie s—. The way it started, the way I came up, the woman I married, the child I had — there’s no holes.

Where does the pain in your music come from?

I’ve thought about that for a long time. I don’t think it’s the entire answer, but I think if your parents divorced when you were little, for the rest of your life there’s gonna be something inside you that’s broken. My parents’ divorce was pretty rowdy, and I remember a lot of it. And I don’t think those things ever fully go away.

How do you think about the relationship between masculinity and stoicism?

It never crosses my mind.

Is your dad a guy who talks about his feelings?

F— no.

Was he scary?

I think he could be. My dad’s the s—. He’s the baddest son of a bitch I’ve ever met in my life.

What image of masculinity do you want to project for your son?

When I think about raising Major, I just want him to want to win. Can fully understand you’re not always going to, but you should always want to, no matter what’s going on. I hope he’s a winner.

When’s the last time you cried?

Actually wasn’t very long ago. A good friend of mine died — Ben Vaughn, who was the president of my publishing company in Nashville. I played “L.A. Freeway,” the Guy Clark song, at his memorial service a couple weeks ago. That got me pretty good.

You said you’re OK if fans don’t like this record.

I don’t need anyone else to like it. I hope that they love it — I hope it hits them right in the f—ing gut and that these songs are the ones they go listen to in 10 years when they want to feel like they did 10 years ago. That’s what music does for me. But I know not everybody feels music as intensely as I do.

Was that true for you as a kid?

Even 6, 7, 8 years old, I’d listen to a song on repeat over and over and over again. I can’t explain how deeply emotional songs make me — it controls my entire being. The right song in the right moment is everything to me. Where I live, there’s a road called River Road, in the Hill Country in Texas. It’s the most gorgeous place you’ve ever been in your life, and I’ll go drive it. I know the exact minute that I should be there in the afternoons at this time of year to catch the light through the trees, and I’ll have the songs I’m gonna play while I’m driving that road.

You know what song you want to hear at a certain bend in the road.

Probably a little psychotic.

Are you one of these guys who wants the towels to hang on the rack just so?

I like things very clean and organized.

Is that because you grew up in that kind of environment or because you grew up in the opposite?

My mom was very clean and organized. But I don’t know — I’ve never one time gone to bed with dirty dishes in the sink. My wife cooks dinner all the time when I’m home, and as soon as we’re done, I do all the dishes and load the dishwasher and wipe the counters down.

You could never just chill and let it go.

No, it’s messy. It’s gross.

Parker McCollum performs at the Stagecoach festival in 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Do people ever interpret your intensity as, “This dude’s kind of a d—?”

People would always tell me I was cocky, and I’d be like, I don’t feel cocky at all. I was raised to have great manners: take my hat off when I meet a lady, look somebody in the eye with a firm handshake, “Yes, ma’am,” “No, ma’am,” “Yes, sir,” “No, sir,” no matter the age or the gender of the person. Manners were such a crazy thing in my childhood — it’s the only way I know how to speak to people. So I’ve always thought it was so weird, in high school, girls would be like, “Oh, you’re so cocky.”

I mean, I’ve seen the “What Kinda Man” video. You obviously know you look cool.

I don’t think that at all. I think I look kind of dumb.

I’m not sure whether to believe you.

I couldn’t be more serious. This is very weird for me to say, but Frank finally put into words what I’ve always felt with every photographer, anybody I’ve ever worked with in the business since I was 19 years old — he said, “This record sounds like Parker’s heart and mind and not his face.” The fact that I’m not 5-foot-7 with a beard and covered in tattoos — it’s like nobody ever thinks that the songs are gonna have any integrity.

Boo-hoo for the pretty boy.

People always called me “Hollywood,” “pretty boy,” all this stuff. I guess it’s better than calling you a f—ing fat-ass. But I’ve never tried to capitalize on that at any point in time. I’ve always just wanted to be a songwriter.

But you know how to dress.

Kind of?

Come on, man — the gold chains, the Lucchese boots.

That’s all to compensate for the fact that I don’t know what the f— to wear. I know I like gold and diamonds. Loved rappers when I was younger. Waylon Jennings wore gold chains and diamonds, Johnny Cash did — they always looked dope. I was always like, I want to do that too.

If the fans’ approval isn’t crucial, whose approval does mean something to you?

George Strait. John Mayer. Steve Earle. My older brother. My dad.

You know Mayer?

We’ve talked on Instagram.

Why is he such a big one for you?

The commitment to the craft, I think, is what I’ve admired so much about him. It’s funny: When I was younger, I always said I was never gonna get married and have kids because I knew John Mayer was never going to, and I really respected how he was just gonna chase whatever it is that he was chasing forever. Then he got into records like “The Search for Everything” and “Sob Rock,” and he kind of hints at the fact that he missed out on that — he wishes he had a wife, wishes he had kids. That really resonated with me. I was like, all right, I don’t want to be 40 and alone. It completely changed my entire perspective on my future.

You played “Courtesy Of The Red, White And Blue” by the late Toby Keith at one of Donald Trump’s inaugural balls in January. What do you like about that song?

I bleed red, white and blue. I’m all about the United States of America — I’m all about what it stands for. A lot of people get turned off by that nowadays. I don’t care — I’m not worried about if you’re patriotic or not. But Toby was a great songwriter, and I love how much he loved his country.

In that Texas Monthly interview, you said you felt it was embarrassing for people to be affected emotionally by an artist’s political affiliation.

Nobody used to talk about it, and now it’s so polarizing. Am I not gonna listen to Neil Young now? I’m gonna listen to Neil Young all the f—ing time.

Why do you think audiences started caring?

Social media and the constant flood of information and political propaganda that people are absorbing around the clock. It’s just so dumb. I’ve got guys in my band and in my crew that are conservative and guys that are liberal. It makes no difference to me.

Of course you knew how your involvement with Trump would be taken.

Think about being 16, wanting to be a country singer, then getting to go play the presidential inauguration. What a crazy honor. There’s not a single president in history who was perfect — not a single one that didn’t do something wrong, not a single one that only did wrong. I just don’t care what people think about that stuff. Everybody feels different about things, and nowadays it’s like two sides of the fence — you either agree with this or you agree with that. I’m not that way.

What do you think happens next for you?

This is the only record I’ve ever made that I didn’t think about that as soon as I walked out of the studio. I have no idea what the next record is gonna be. Not a clue.

If we meet again in two years and you’ve made a record full of trap beats, what would that mean?

Probably that I was on drugs again.