Aaron Moore was at his workshop in Garden Grove when the first wave of pain hit.

That fall morning in 2022, the furniture refinisher, who was 36 at the time, felt his limbs begin to tingle as he took the clamps off a table. He had been under elevated stress. He was juggling care for a busy toddler and a booming business, along with building a social media presence to promote his work.

In this series, we highlight independent makers and artists, from glassblowers to fiber artists, who are creating original products in Los Angeles.

So as the tingling escalated to moderate chest pain, Moore chalked it up to a panic attack and kept working.

It was only upon seeing a late friend’s funeral program pinned above his desk that Moore caved and headed to the hospital. Two weeks later, his doctor told him that decision likely saved his life.

“In the hospital, it was a joke, because we didn’t really know what was going on,” Moore said. After being told that he’d had a trio of NSTEMI heart attacks (characterized by partial blockage in a coronary artery), he was still unsure how serious they had been.

-

Share via

At his two-week follow-up, though, Moore said he learned those “mini heart attacks” could have been precursors to a deadly finale.

“It was more of a, ‘Hey, you just narrowly dodged the widow-maker,’” he said.

At home in Orange, Moore didn’t have much time to process the episode. His toddler son and newborn daughter kept him plenty busy. However, back in the shop, amid the mesmeric hum of sanders and drum fans, a thought dawned on him: “What would have happened to all the knowledge if I had died?”

Aaron Moore has managed his own refinishing business in Orange County since 2010.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

A high school woodshop prodigy, Moore got his start in furniture refinishing at a piano company in Anaheim. His boss, a friend’s dad, hired him just before he graduated from Esperanza High School, and he stayed at that job for about five years.

Moore loved the work, but he hated workplace politics. He wanted to get poached by another refinisher based in Garden Grove. That refinisher’s name was Butch Crane, but Moore liked to call him Elmer Fudd after Bugs Bunny’s antagonist from Looney Tunes: “Bald, kind of chunky, wore the red plaid flannels.”

When Crane decided to retire in 2010, he was resolved to keep the building out of the city’s hands. So he made Moore a deal.

Aaron Moore has for more than two decades refinished diverse pieces, from family heirlooms to fine art installations.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

“Five grand. I’m leaving in one month. If you want it, shop’s yours,” Moore recalled Crane telling him.

Moore accepted.

Fifteen years later, the tradesman stood outside Crane’s old spray booth, sanding a $25,000 rosewood bench.

“Rosewood has a very floral scent to it,” he said. “You can smell it in the air.”

“There’s more than enough people out there that need these services, and I turn a lot of work away,” said Aaron Moore, who has amassed high-profile clients from specialty collectors to fine art dealers.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

Above him hung a “Moore’s Refishing” sign, a friend’s comical misspelling of the shop’s name.

Tucked into a corner of industrial Garden Grove, Moore’s Refinishing boasts no ornate exterior. The shop’s only signage — save for the misprint in the back — graces the top half of its glass front door.

Inside, though, is every thrifter’s Midcentury Modern dream. Atop a wooden mezzanine, a rattan back desk sits among chestnut-colored dining chairs. Deeper into the shop, a Grotrian-Steinweg piano is just put back on its legs.

When Moore first took over the shop, he worked mostly on antiques, or as he calls it, “grandma’s old furniture.”

Over the years, he’s amassed high-profile clients from specialty collectors to fine art dealers. His most expensive project thus far is a rare Antoine Philippon & Jacqueline Lecoq wall unit that Laguna Beach gallery owner Peter Blake valued at $175,000.

Many of Aaron Moore’s clients are specialty collectors whose mission is to acquire unique items including vintage pianos.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

At 38, Moore has spent more than half his life in a trade boasting no more than a handful of old-timers to preserve it. After his 2022 health scare, he has been more intent than ever on passing down all he’d learned, but he wasn’t sure how.

That’s when Anastasia Petukhova wound up at his doorstep.

Petukhova, a Moscow-born marketer and photographer, was teaching marketing classes part-time at Loyola Marymount University when she began flipping furniture as a social experiment to share with her students.

At some point, Petukhova said, “my flipping sort of evolved from something very basic to some nicer pieces,” and she realized she needed a master to fill in her knowledge gaps. So she started doing her research.

Moore’s Refinishing is packed to the brim with mid-century furniture, pipe clamps and drawers of miscellaneous tools. (Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

“Turns out there’s this guy, Aaron Moore, an hour away from me,” Petukhova said. She messaged him, offering a free photo session in exchange for a refinishing lesson.

“I thought, I show up for half a day, do the skeleton of the process,” she said. “How difficult can it be?”

They met a few days after Moore’s cardiac episode. Moore knew it wasn’t wise to return to work so soon, but he’d already canceled on Petukhova twice. He didn’t want to bail again.

The pair ended up working together for more than a year on Petukhova’s furniture flips, Moore’s online refinishing content and later the coffee table book of Petukhova’s dreams.

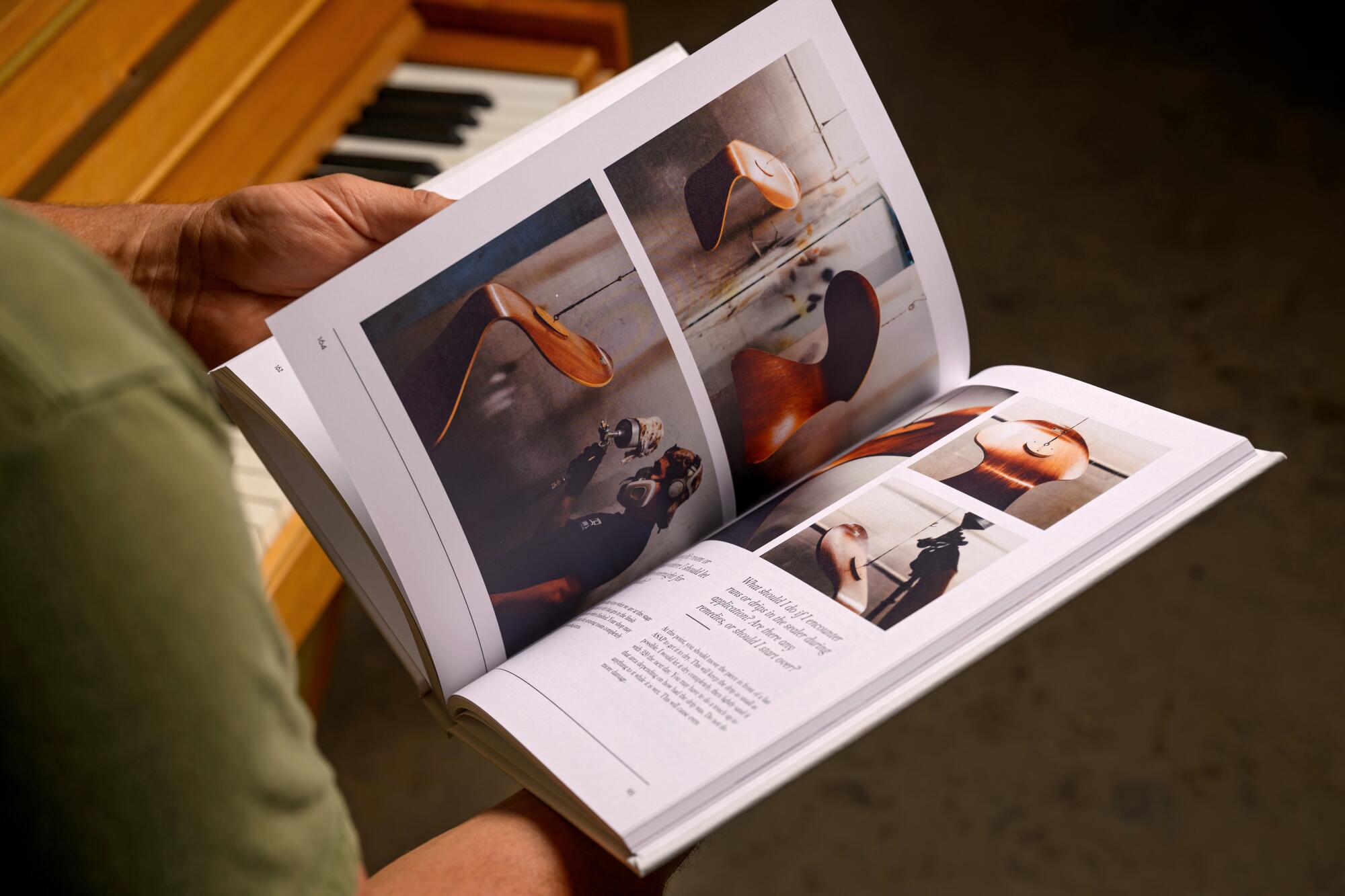

“Revive and Refine: The Art of Furniture Restoration” (self-published last year and available on Moore’s website for $125) is a 240-page starter guide for aspiring refinishers, covering everything from the basics of disassembly to master staining techniques. It’s intentionally written in such a way that anyone can pick it up and get started on a project — Moore’s wife scanned his manuscript for jargon before the book was published.

In the book, Petukhova’s images depicting the refinishing process step-by-step are interspersed with fine art-style photographs. The cover image, chosen by Moore’s social media followers, is a striking shot of a 1970s Afra and Tobia Scarpa dining chair, so aesthetically composed that the object itself is defamiliarized, taking on the visual quality of an ancient relic.

Aaron Moore regularly works on vintage wooden pieces dating back to the 1970s.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

When Moore first entered the industry in the mid-2000s, he said his mentors habitually kept trade secrets. “This was an industry of gatekeepers,” he said, adding that master tradesmen ultimately viewed their apprentices — working in the same 10- to 15-mile radius as them — as competition.

However, in the internet age, there’s business enough for everyone, Moore said, and teaching others what he knows doesn’t threaten his own livelihood. If anything, it preserves his legacy at a pivotal moment for skilled trades.

Enrollment at public two-year schools focusing on vocational and trade programs has risen by nearly 20% since the spring of 2020, according to a May National Student Clearinghouse report. One explanation for this upward trend is the majority belief among Gen Zers that a college degree isn’t necessary to obtain a well-paying, stable job.

Moore’s mission is to capitalize on this resurgence of interest in the trades. He started to notice the uptick on his social media channels, especially after he first started sharing refinishing content on Instagram in 2021. He’s since expanded his content by posting longer form videos on YouTube and teaching a paid online course that has 100 members.

Moore films most of his online content during the work day, which he admitted has caused some projects to pile up.

Blake, the gallery owner, has begun calling Moore “Aaron Kardashian” — a dig at what he called the refinisher’s growing “influencer” behavior.

“I love giving him s— about [it], you know, when I walk in there and see the tripod,” Blake said. “I tell him that, ‘Of course, my stuff isn’t done, because you’re so busy being an influencer.’”

But like the vast majority of Moore’s clients, Blake is mostly content to wait, knowing his go-to refinisher has never skimped on quality.

“I hate to say this, but I pushed the s— out of him,” Blake said. “I would give him threats all the time that, ‘It better be good, Aaron. You realize this is a $30,000 chair. Do not f— it up.’

“I gotta say, he rose to the occasion,” the gallerist said.

Aaron Moore said his customers don’t mind long wait times because “they know it’s going to be done properly.”

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

Ivan Astorga, Moore’s only full-time employee, initially had trouble adjusting to his boss’ high standards. He began working part-time at Moore’s Refinishing in 2016, while still employed at his father-in-law’s refinishing business. A couple years in, Moore realized Astorga had downplayed his skills and promoted him to full-time.

“Working here was a complete different ballgame. He demanded only the best for his clients,” Astorga said.

At the shop earlier this month, Astorga was making his fourth pass on a chipped wooden table. Several times, he worked a Walmart iron over a wet cloth, then peeled the fabric back to inspect the surface underneath. On the last round, the chip was hardly visible.

To this day, whenever Astorga visits his father-in-law’s shop, he said he has to hold his tongue about stains and scratches Moore would never miss.

In the rare event Moore does make a mistake — like the time he sanded through the veneer on a coffee table — “we have the capabilities to repair it after,” he said.

Sometimes, he added, “you have to break things first before you can make them better.”

Aaron Moore wrote “Revive and Refine: The Art of Furniture Restoration” as a starter guide for aspiring refinishers.

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

Moore said that as a kid growing up in Yorba Linda, he always loved the physicality of taking things apart and putting them back together. But it’s not the work itself that has kept him in the industry; it’s the stories.

Pacing across his workshop, Moore rattled off the names of clients with heirlooms in his queue, smiling as he spoke about one woman who brought in her childhood sewing machine for restoration.

Just outside his office, he’s curated a Wall of Treasures, composed of miscellaneous objects he found in furniture purchased at auction. Among the bric-a-brac are a hosiery stock card, old negatives and a birthday letter.

“It’s history,” Moore said. “I’m a catch-all person for this, not junk wood.”

Moore doesn’t see himself retiring any time soon. No one currently stands to replace him, but he’s hoping that the supplemental income he derives from his online and in-person coaching side hustle will allow him to spend fewer hours in the shop.

“I’m tired of doing it to this degree,” Moore said, adding that he’d rather make the bulk of his salary teaching refinishing than doing it himself.

Aaron Moore flips through his book “Revive and Refine: The Art of Furniture Restoration.”

(Ron De Angelis / For The Times)

That plan looks promising as he gears up to send a $20,000 quote to a prospective coaching client. To him, the figure seems inordinate. But to his wife Taylor, it represents the true value of his labor.

“My whole family is attorneys,” said Taylor, a probate paralegal. “They’re looking at it from, ‘What is your hourly rate? How long is it going to take you to do this? What would you make in the shop?’”

Taylor, 33, added that her husband can sometimes underestimate the value of what he does because “it’s such a lost art.” “He doesn’t realize what he does is so unique, and no one really does it anymore,” she said. “All the old-timers are either retired or have passed or slowed down.”

Financially, it would behoove Moore to keep the trade specialized and therefore more lucrative for himself. But that’s not the future he wrote a book for.