Welcome to this new post about my personal growth on the PCT, now that I’ve made it Through the Spine of the Mammoth and finally arrived in the town of Mammoth Lakes. I had just completed one of the most challenging sections of the trail and possibly of my life.

Now it’s time to share how my journey continued from there. So without further ado, let’s dive in.

I woke up that morning at the campground, carefully packed my gear, and sat at a picnic table to enjoy my breakfast.

While I was checking my phone, I noticed the camp host stepping out of his RV. Still in his robe, he climbed into his truck, drove the 20 meters that separated his van from my table, and stopped right in front of me.

I assumed he wanted to talk, so I stood up and walked over.

The Camp Host

A camper at RV campground

— Good morning! How did you sleep? Just a reminder—you need to leave early, try to do it before 9am. he said.

— Morning! Yes, I slept well, thank you. My pack’s ready, I’m just finishing my yogurt here at the table, I replied.

— Oh, no problem then. I thought you still had to pack up. Take your time. Best of luck on the rest of your journey, hiker.

I thanked him, he rolled up his window, and drove about 15 more meters to a vacant campsite. There, he maneuvered the truck to turn around and face the opposite direction—on the same road we had just been talking on.

By the time he passed me again, I was already back at the table, finishing my yogurt. I thought he might’ve forgotten to tell me something and was coming back. But no.

Instead, he drove back to where his RV had been parked originally, shut off the engine, stepped out still in his robe, and went back inside.

Strangely Normal

I watched this whole little scene unfold like someone peeking out their window, spying on the neighbors.

That’s when it hit me: he’d made that whole round trip just to talk to me.

It was only 6 a.m., and I had told him the day before that I planned to leave no later than 8. He had said that would be totally fine.

Maybe that was just his way of saying goodbye—maybe he saw me through the window and wanted to check if I was on my way out.

Who knows what really motivated him to go through all that trouble with his truck when he could’ve simply walked the distance.

Then it dawned on me: maybe I’m the weird one.

After all, I’ve been walking from the Mexican border for two months now. Maybe that little sensor in my brain that calculates “this is driving distance” just broke along the way.

The Mountains Are Calling and I Must Go

I quickly finished the rest of my yogurt, grabbed my backpack, and walked to the bus stop. The red line bus showed up almost immediately, and I was on my way back to Horseshoe Lake.

I greeted the driver, who looked a bit surprised to be picking someone up at the first stop on the early morning route.

— You must be heading into the mountains, huh? I’ll drop you off at The Village, then you can catch another line from there to go up.

— Exactly, thank you! That’s my destination.

I sat in the first seat behind the driver as we continued the route. Like in many mountain towns, bus rides were free—which was great for my budget.

My Pace

I pulled out my phone and went over the trail options ahead. I had resupplied for about six days—more than enough to make it to my next destination. Or was it?

My resupply

Here’s the thing: since the start of the PCT, I had planned to push hard in the desert section so I could spend more time in the Sierra Nevada.

Time-wise, I was doing well. A lot had happened along the trail, and I had taken more zero days than expected. Still, I was only one day behind schedule.

Why? Because by now, my body was capable of hiking 25 to 30 miles a day, which meant I could reach resupply points sooner than expected.

In the Shadow of the Dome

One place I really wanted to visit was the famous Yosemite National Park. The truth is, I didn’t really know much about what to do there or how the park worked.

I did some research and found that the main hub is called Yosemite Valley—a sort of basecamp from which people can go out and explore.

I read some reviews and blog posts, many of which talked about waterfalls and towering granite walls visible from the valley.

They all mentioned The Cap which reminded me of that insane climbing documentary where the guy climbs it free solo. Total madness—not something I’d ever attempt.

Another name kept popping up: Half Dome. I looked into it and really liked what I saw. It’s a tough climb, but the panoramic view from the top is stunning.

Then came the letdown: you needed to enter a lottery to get a permit for the climb. You had to be selected for a specific date. As a nomad with no fixed itinerary, that made it nearly impossible.

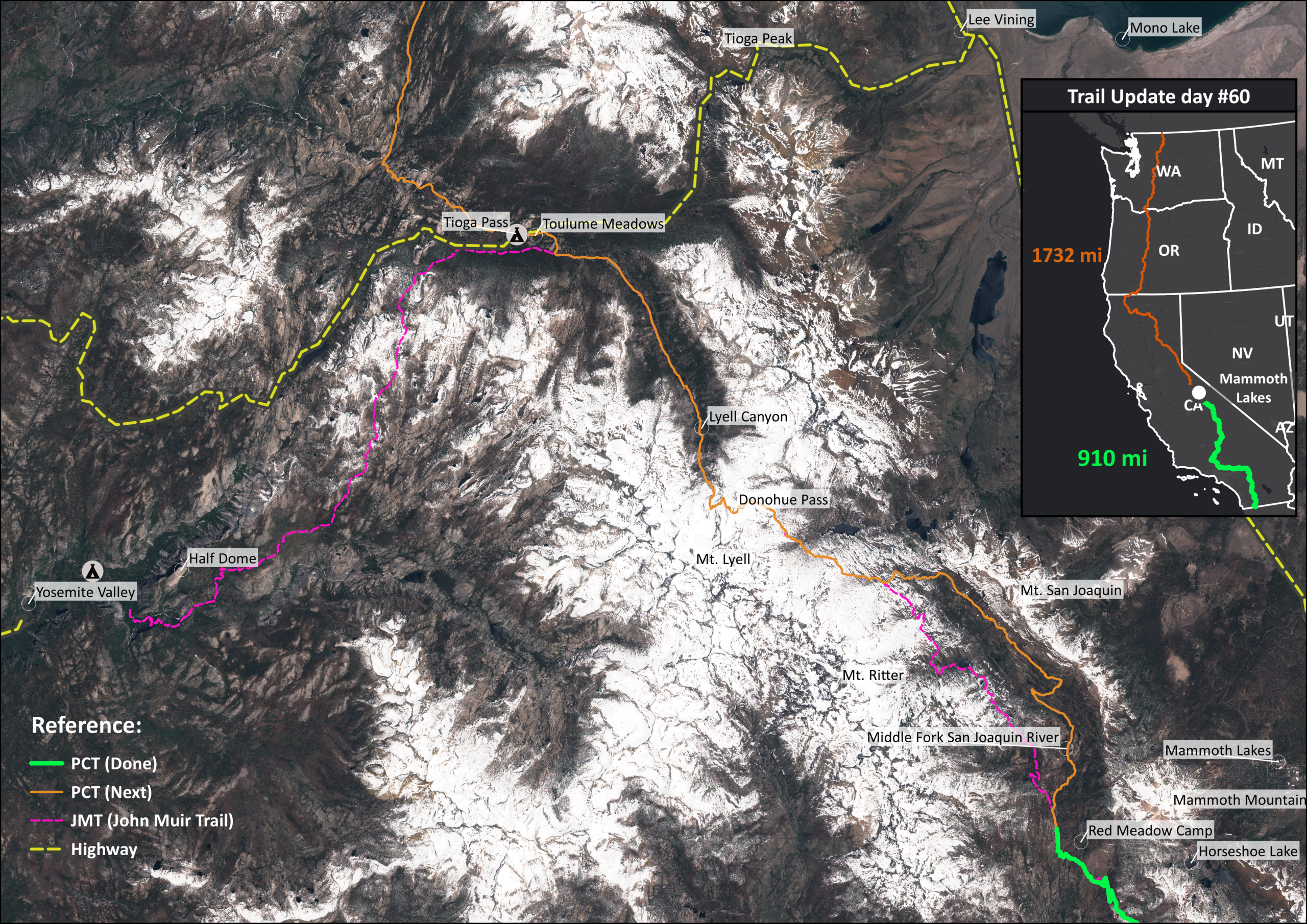

Trail Update

Trail Update day 60: from Mammoth to Yosemite Valley

Getting There: On Foot?

I looked into how to reach Yosemite Valley. One option was hiking in from a place called Tuolumne Meadows. It was about 50 more kilometers—tough on my legs, but doable.

But that wasn’t all. To hike that trail, you needed a permit for the JMT (John Muir Trail).

Some hikers claimed the PCT permit gave you “superpowers,” but apparently those powers didn’t cover access to Yosemite Valley via the JMT.

Getting There: By Car

The other option was to get to Tuolumne Meadows and then keep going along the road to a place called Tioga Pass.

From there, Tioga Road serves as the main gateway into Yosemite Valley from the huge Owens Valley—where towns like Bishop, Lone Pine, and Mammoth Lakes are located.

The only problem? Tioga Road was still closed for the season.

There were rumors it might open soon, so I’d have to wait and see when I got there—which I expected would be in about two days.

Wrong Trail

While I was still weighing my options, I kept walking along the PCT. I had just returned to the trail at Horseshoe Lake after three days away.

My energy was renewed—so much so that each step flowed effortlessly into the next. I hadn’t started as early as usual, but the timing was still reasonable. I had already eaten a quick lunch I’d picked up at a Target store.

In the midst of all this distraction, I didn’t notice that I’d taken a different route than the one I’d used to get to Mammoth Lakes. I was walking along a well-marked trail, surrounded by fallen trees, which offered sweeping views of the valley ahead.

View of Devils Postpile National Monument

I checked my phone and saw that I was on a trail called the Old John Muir Trail. Although it veered slightly north, it would still take me to the same destination—a campground called Red Meadows Campground.

Red Meadows Campground

The trail began to descend steeply, and I passed several people who looked like they were working in the area near the campground. Among them, I ran into a French guy hiking the trail. When he saw me, he stopped and asked if I had been walking for long.

I told him I had started at the Mexican border, about 1,400 kilometers behind me. His eyes widened in disbelief when he learned there was a trail that long. I shared that my final goal was to reach Canada, though there was still a long way to go. But with every step, the dream was becoming more and more real.

He wished me luck on my journey, and we said goodbye. A few minutes later, I reached the entrance to Red Meadows Campground.

Entrance sign to Red Meadow Resort

This was the spot Slippy and Ulrik had mentioned—they planned to hike down to Mammoth Lakes to resupply and return to the trail the same day to keep moving north. I had spent three days off-trail, so they were likely quite a bit ahead of me by now, probably near Tioga Pass.

An Unexpected Message

As I walked toward the campground’s grocery store, my InReach buzzed—I had received a message. I grabbed a few chocolates and a beer and sat down to read it.

Drinking a beer at Red Meadows Campground

I popped open the beer and picked up my InReach.

To my surprise, it was a message from Saida:

—Diego, we left Red Meadows this morning. We’re heading to Yosemite in two days via Tioga—it’s supposed to open that day. Where are you?

My heart skipped a beat. My friends had been sitting in the very same spot where I was now, just five hours earlier. The message must have been delayed due to poor signal.

But the important part was this: they were ahead of me, and their plan aligned with mine.

I quickly wrote her back. I told her I was at Red Meadows and about to start hiking. I might be able to reach Tioga Road in two days too—though probably a bit later than them, since the day was already quite advanced.

I finished my beer, packed up my gear, and hit the trail once again

Another Broken Bridge

Once again, the PCT had a collapsed bridge—another casualty of the heavy 2023 snow season. This one was just ahead of me, crossing the now-familiar Middle Fork of the San Joaquin River.

Fortunately, this time the detour was much clearer than the last one. The PCTA suggested following a nearby road instead—Minaret Summit Road.

Minaret Summit Road

This detour was going to add some miles, since the PCT normally crossed the river by bridge and rejoined the same side I was currently on about 8 miles later, near a place called Agnew Meadow Road.

You Don’t Like It

The road was completely deserted. I didn’t see a single vehicle, nor any sign that one had recently passed. There were fences and small cabins scattered among the trees, maybe one every 300 meters. It was strange that no one was around.

There were even bus stops along the way, which made the emptiness even more surreal. Walking on a road like this felt incredibly boring. Sure, it was easy and didn’t burn much energy—but mentally, it wore me down.

Maybe it’s because I lose that deep connection with nature. It’s like my mind flips into a different mode—focused only on getting there, reaching the next checkpoint. I start to feel the weight of my backpack more intensely. I keep adjusting it, over and over. I stare at the curve ahead, and when I finally reach it, all I see is another endless straightaway.

It’s odd, because in the mountains, it also takes hours for the scenery to change. Sometimes you’re slipping in snow or trudging uphill in silence. That’s way harder on the body—but somehow, walking a flat road felt more exhausting for the mind.

The Half-Empty Road

With every twist and turn, through all those empty houses and tire tracks in the dirt, I suddenly found myself singing.

La ruta semi vacía, como mi vida sin vos | The road feels so empty, like my life without you.Quién hubiera imaginado | Who would’ve thought the moment would come—Que llegaría el momento | That damned moment of looking to my side, Ese maldito momento de mirar para un costado, | And not seeing you in my mornings,

Y no verte en mis mañanas ni sonreír con tu voz… | Not hearing your laughter…

I was singing a song from No Te Va Gustar (You Don’t Like It). Okay, not just singing—belting it out. I never listen to music on the trail, but singing fragments from memory? That I do.

Something in that moment triggered the song. Deep inside, I was still processing, still healing. Old stories, old wounds that leave their mark—and slowly, over time, you start to let them go.

I don’t think “getting over it” is the right phrase. I think what actually happens is… you start to accept it. And little by little, you understand why those things—those things you thought would never happen—actually did.

Parallels

These things happen on trail. All the time in the world to think. The environment, the silence, the rhythm—it all pulls memories to the surface.

In that moment, I felt like I was walking in the footsteps of Emiliano Brancciari, the lead singer of No Te Va Gustar, balancing that fine line between raw emotional reflection and vivid, physical imagery.

¿Será sólo mi torpeza, o será mi forma de andar? | Is it just my clumsiness, or is it my way of walking?No pude seguir tus pasos | I couldn’t keep up with your steps,Me fui cayendo a pedazos | I crumbled to pieces,Sólo quedaron retazos y no los pude juntar | And the scraps I was left with—I couldn’t put them back together

We try to shape our lives in the way that seems best—or maybe just the way that feels possible. Often, we drift away from who we really are.

And the drift is so gradual that we still feel like we’re in the same place… but we’re not.

We’re walking.

We’re moving forward.

We’re changing.

Changes

Even if it doesn’t feel like it, we’re constantly making choices. Constantly choosing a path.

Sometimes that path is well-worn, followed by many. But maybe it’s not your path.

Si no estás en mis mañanas, | If you’re not in my mornings,

si no me río con vos | If I’m not laughing with you,Si me siento acorralado | If I feel cornered,Es por no haber apreciado | It’s because I didn’t appreciate what life had given me—Y yo mismo haber tirado lo que la vida me dió | And I was the one who threw it all away.

And then—something changes. Something breaks.

Suddenly, the road you were on disappears.

You lose your purpose. Everything you’d been standing on vanishes.

You feel lost. Like you’ve failed. Like all your progress meant nothing.

The Trail

It’s like blinking and suddenly finding yourself back in your hometown, as if none of the PCT ever happened.

Like those 1,400 kilometers just slipped through your fingers like water.

But is that really true?

Did everything vanish overnight?

Sure, maybe you missed a viewpoint. Maybe you didn’t make the smartest resupply decision.

Maybe you had an unfinished conversation that still stings.

But it’s completely absurd to think you haven’t made progress. That everything was for nothing. That your purpose is gone.

The trail, in its brutally honest simplicity, shouts back at you:

That’s not true.

It even feels laughable to believe it.

Because the PCT is that: a raw, simple version of life that somehow makes my mind feel clearer, more grounded, more present.

Keep Moving

With my head full of these reflections—of past pain and lost purpose—I kept walking.

Eventually I reached a muddy, mosquito-ridden climb. I pushed through it, and the trail started to follow the side of a mountain.

My thoughts stayed with me.

I thought about what had brought me down in my regular life—the sadness, the sense of failure.

And I realized… it had to happen.

But that didn’t mean I hadn’t grown. Or moved forward. Or accomplished anything.

Because in the end, what is progress?

What’s right and what’s wrong?

What’s the point of building a house or a family if you’re not happy enough to enjoy it?

Just because “everyone” goes in that direction…

doesn’t mean it’s the right one for you.

Time to Rest

Around 8 p.m., I decided it was time to stop walking for the day.

My trail kitchen for the night

I hadn’t made it to my goal—Thousand Island Lake. The name alone sounded like something from a dream.

But I didn’t feel like hiking into the night. There were still quite a few kilometers to go.

Did that make me a failure?

Was I defeated because I didn’t pitch my tent with some picture-perfect lake view?

I sighed, laughed, and answered myself:

Of course not.

I was in an incredible place. I had covered a solid stretch of trail today. Maybe I hadn’t reached that specific lake—but I would tomorrow.

More importantly, I had moved forward spiritually. I had faced some of those lingering old wounds.

My body felt strong, so I prepped my classic Ramen Bomb and got ready to rest.

Tomorrow, I might reunite with my trail family.

And maybe—even more incredibly—I’d finally step into Yosemite Valley.

And the craziest part?

I’d walked there.

From the Mexican border.

Thousand Island Lake

I woke up early and began my daily ritual—pulling my arms out of my sleeping bag, stretching my back, letting out a long “Ahhh” with a yawn, clicking my tongue, and digging inside my bag to find my hiking clothes, still warm from the night.

Once dressed, I packed up all my gear, loaded my backpack, and hit the trail.

A few hours into the hike, the morning sun lit up the surrounding landscape—and there it was: Thousand Island Lake.

First Glimpse of Thousand Island Lake

Snowcapped mountains framed the scene, and the frozen lake stretched wide, dotted with rocky islets breaking through the icy surface like tiny floating fortresses.

Breakfast Time

I hadn’t had breakfast yet, so I found a nice spot with a view and pulled out my overnight oats. As I sat down and ate, I noticed a few people closer to the shoreline—some lounging in the sun, others emerging from their tents.

View of Banner Peak over Thousand Island Lake

From a distance, I spotted my friend Roadrunner by her tent, calmly scrolling on her phone—probably filming content for her YouTube channel. I didn’t want to interrupt her moment, so I stayed on my rock and enjoyed my meal in silence.

Saida had mentioned they’d be camping at this lake. But since I didn’t see a group of tents, I assumed the crew had already moved on.

So I packed up and continued—there was still a mountain pass ahead, and that’s never something to underestimate.

Donohue Pass

From the lake, the trail started a steady climb. Snow appeared quickly, but it was shallow and packed. When it gave way, my boots immediately hit rock.

Soon the entire trail was snow-covered, but the path toward the pass was obvious. I followed my instincts, heading for the saddle in the horizon. In the distance, the blue Sierra peaks began to rise, signaling that I had conquered yet another high pass.

View from Donohue Pass

The view from Donohue Pass was breathtaking—granite mountains fading into the distance, with patches of lingering snow. The melt was well underway, making this one of the easier passes I had encountered in the Sierra.

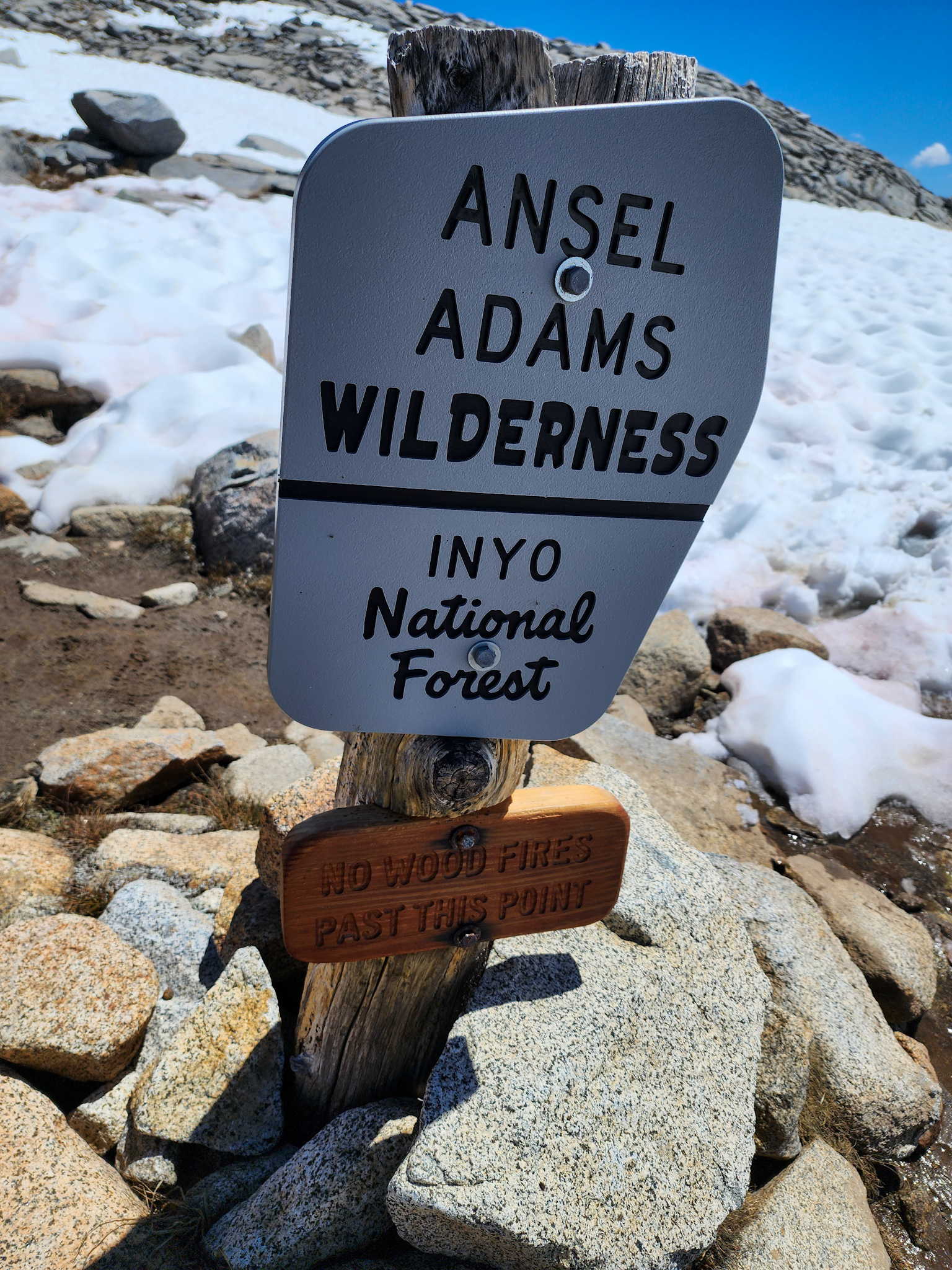

Lyell Canyon

As I crossed the top, a vast valley opened up on the other side. Towering granite walls marked the boundary of a new realm.

I Made It!

There was no mistaking it. What lay before me was the Lyell Canyon, and beyond that, the granite ridge had to be the Tioga Pass Range.

I paused for a moment.

Diego, I told myself, you’re at the doorstep of Yosemite National Park—the place everyone talks about, a place that once felt impossibly out of reach. But here you are. You made it on foot, from Mexico.

Cous cous lunch

It hit me. The reality of that moment knocked the wind out of me. I felt overwhelmed with gratitude and pride. My backpack had traveled with me from Uruguay to San Diego—and from there, every step had brought me here.

Lyell Canyon

I began descending from the pass and quickly dropped below the snow line. The terrain turned muddy, with low vegetation that reminded me of the mallines in the Argentine Andes.

Mallines of Lyell Canyon and Donohue Pass behind

My legs moved effortlessly—light and quick. I had no idea where this sudden energy came from, but I embraced it.

Big News

Then, the familiar beep beep of my InReach broke my momentum. I unhooked it from my shoulder strap.

It was Saida.

– Mile 937! In two hours we’ll be at Tioga Road and hitching into Yosemite Valley! The road just opened today!

That message was pure magic. The mystical feeling of “The Trail Provides” came over me again. Not only was the road open—but I was just three miles behind my trail family.

I wrote back:

– I should get to Tioga Road in about three hours. See you in Yosemite!

Let’s go legs!!! WE DID IT

Storybook Forests

The trail alongside Lyell Fork was like something out of a dream.

Foto: Bosques al lado del Lyell Fork

A deep green forest enveloped the trail, filled with Lodgepole pines—tall, straight trunks with paper-thin bark and long, dark needles like Christmas tree branches.

The harmony of the landscape was unlike anything I’d seen. It felt untouched—pristine. Deer grazed peacefully across the creek, wandering freely in the meadows. The Leave No Trace principles were clearly alive here.

Deers at Lyell Canyon

Tuolumne Meadows

Eventually, I reached a sign pointing to Tuolumne Meadows Campground. It was technically closed, but a park ranger appeared on the trail.

– Hey! You’re a PCT or JMT hiker, right? The campground’s under maintenance, but you can cross through to reach Tioga Road. It opened today!

– Yes, thank you! I’m hoping to hitchhike into Yosemite Valley, I replied.

She smiled.

– That’s a great plan! Just a heads up, though—since they just announced the road reopening, most people already rerouted through the other entrance. Don’t expect much traffic.

Uh-oh

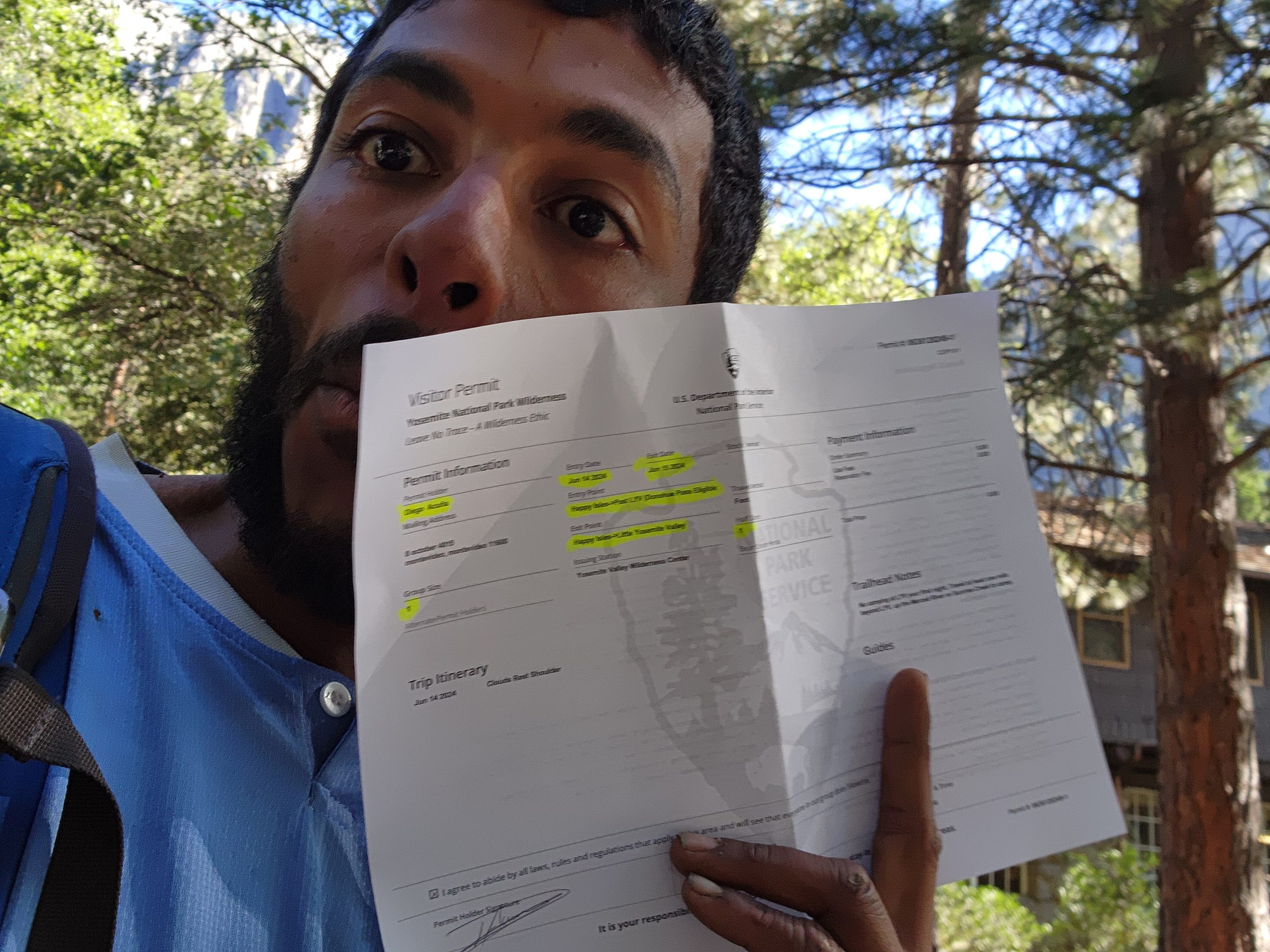

A wave of realization hit me—I didn’t have a permit to enter Yosemite Valley, and my PCT permit didn’t cover that.

Seeing my expression, the ranger added:

-You probably don’t have a Yosemite permit, do you? Try hitching in today or tomorrow. When you get to the entrance, explain you’re a PCT hiker—they usually have a backpacker/biker campsite where you can stay a night. You won’t be able to climb Half Dome, but you can experience the valley. It’s beautiful.

I thanked her and moved on.

I reached the road—it was completely deserted. I started walking east, hoping to find the parking lot about a kilometer away.

Tioga Road

The ranger’s advice was excellent—it gave me a clearer idea of how to approach the situation. As for the Yosemite permit, this wasn’t the moment to stress about it. I figured I’d get there and see what happened.

The real problem was transportation. I opened FarOut to read comments about hitching into the park. There was nothing. Just one message from a girl who said she had started walking the road toward Yosemite, and after four hours a ranger took pity on her and gave her a ride.

That wasn’t exactly encouraging.

Getting to the Parking Lot

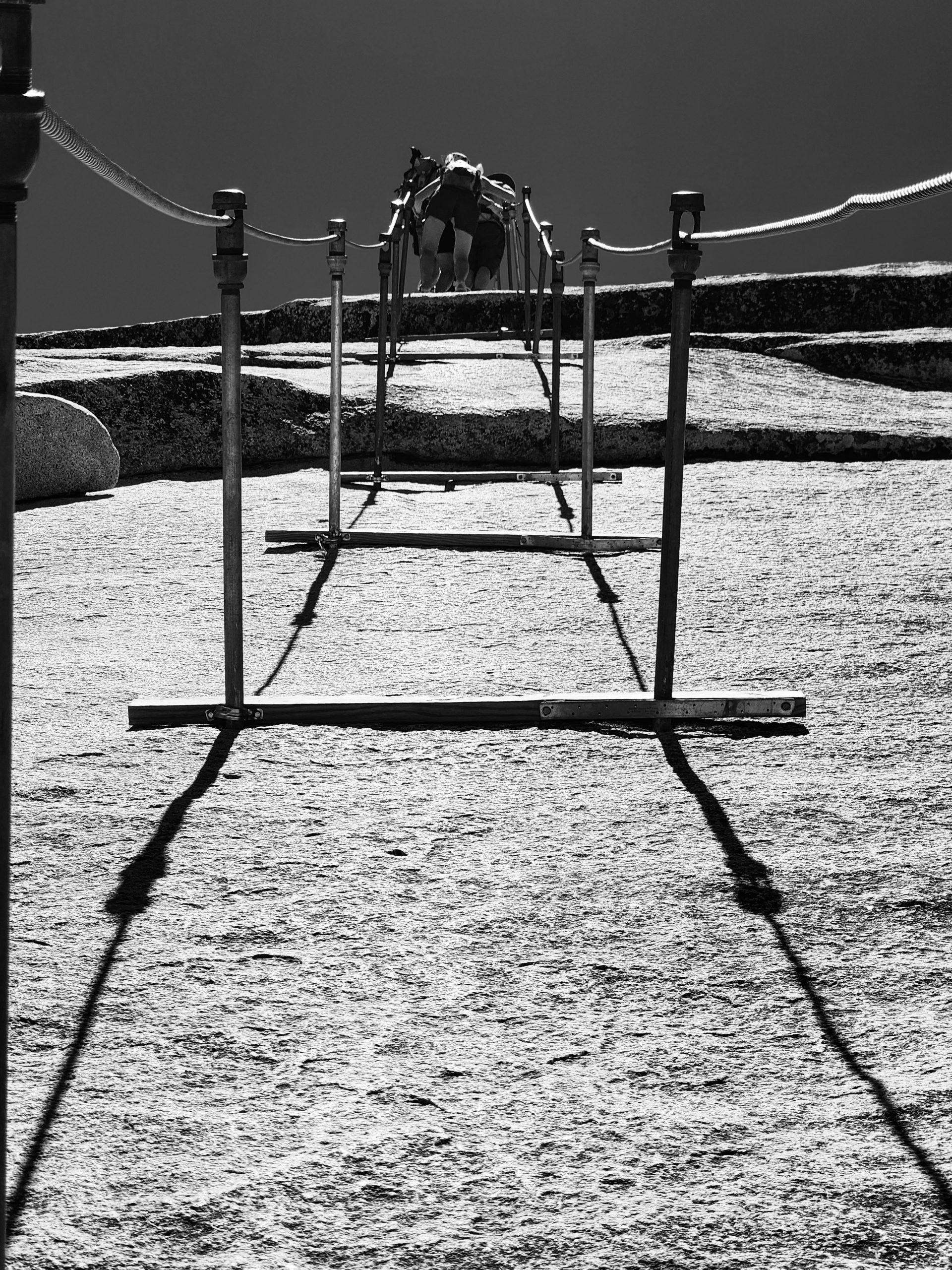

Eventually, I reached a bridge that crossed the Toulumne River. In the distance, I could see another road—this one had actual traffic. The scene was surreal: the bridge, the towering pine trees, and a massive granite mountain that looked like a single colossal rock rising straight out of the ground.

Bridge over the Tuolumne River with Lembert Dome in the background.

I made it to the parking lot and spotted a few cars. I raised my hand to greet a man who was loading gear into his vehicle. He returned the wave and motioned for me to come over.

Hitchhiking Techniques

The most natural way to get a hitch is to stand on the side of the road and do the classic thumb-up gesture. It usually takes several cars to pass by before someone stops—especially on highways, where stopping is often not even allowed.

But there’s another technique that had been working wonders for me. Some might say it’s a bit forward, but it works. I’d simply greet someone already parked and walk over to ask for a ride. My success rate with this approach was sky-high. Sometimes, even when they initially said no, they’d start their car, think twice, and drive back to pick me up. That short interaction often created a connection strong enough to tip the scale.

That’s exactly what I did this time—I walked over to the man who had waved me over.

A Complicated Route

I greeted him, and he responded warmly.

– That backpack looks heavy! Where are you trying to go?

– Haha, yeah, it’s a bit heavy. I’m trying to get to Yosemite Valley. Is that this way?

– Yes, it is. But I’m headed in the opposite direction, toward Mono Lake. Planning to camp at Ellery Lake. I haven’t seen much traffic going into Yosemite today—it just reopened. I hope you get lucky, but I think it’s going to be tough.

I thanked him for his time and kindness, then sat down on a nearby log to think things through. As I pulled out my Inreach, a message popped in—it was from Saida:

– Diego, we’re heading to Lee Vining instead of Yosemite Valley. No one’s going into the park today.

A Change of Plans

That message sealed it. I decided not to go toward Yosemite Valley. It made more sense to head into town, get some rest, and figure things out tomorrow. Then I remembered—this same guy had told me he was going in the opposite direction of Yosemite. Maybe he could give me a lift.

I saw him about to get into his car and ran over to catch him.

He stopped, rolled down his window, and I asked:

– My friends are going to Lee Vining. Is that on your way?

– It’s a bit further than where I was headed, but sure—I can definitely drop you most of the way. Hop in.

Riding Along Tioga Road

The road was stunning. As soon as I got in, the driver said, “This is one of the most scenic roads I know. Lots of people bike it—especially when Yosemite is closed. It’s an amazing experience.”

As we drove through winding curves and mountain passes, I understood exactly why everyone raves about this stretch of road. Around every bend, the landscape changed—from thick pine forests to towering snowy peaks, to sheer granite cliffs with mirror-like alpine lakes.

This road skirts a massive valley that slowly descends from the mountains to the vast Owens Valley, where the tiny town of Lee Vining awaited me.

Rolling into Town

The driver started telling me all about the area. I replied eagerly, soaking in every detail he shared about the local geology and history. I was completely absorbed by the changing landscape outside the window. Though I’d only been in the car for about thirty minutes, it felt like we had crossed through several worlds.

As we reached his original destination, he turned to me and said:

– Let’s keep going. I’ll drop you off in downtown Lee Vining. I want to show you Mono Lake.

Arriving in Lee Vining with a view of Mono Lake.

Mono Lake

He explained that Mono Lake is one of the oldest lakes in North America. It’s fed only by streams and rainfall, and it has no outlet—so all the water exits by evaporation. That concentrates the salts and minerals in the lake, giving rise to its unique chemistry. No fish live there, but it’s home to millions of brine shrimp, which attract migratory birds like the California gull and the phalarope. It’s a key spot on the Pacific Flyway.

This guy was like an open book—a true mountain lover and a fantastic storyteller.

We reached the center of tiny Lee Vining. I thanked him sincerely for the ride and offered him money, but he refused.

– Safe travels, Roadrunner! I hope you find your friends—and tomorrow, that you make it to Yosemite Valley to check off another milestone in your amazing journey.

Another small American town, another unexpected stop that hadn’t even crossed my mind an hour earlier. But there I was. Only about 400 people live in Lee Vining, and the town is built right along the highway. As soon as I arrived, I got cell service and managed to reach Saida! They had found a spot in an RV park where they could pitch their tents.

I headed over, dropped my stuff, and we all went out to eat at a Mexican restaurant in the center of town. It was a well-deserved treat—I was back with my trail family!

Dinner was quick—we were all wiped out. We agreed to catch up on everything the next day.

My hips don’t lie

I got back to my tent and collapsed on my sleeping pad. I wasn’t physically tired from hiking, but mentally drained after the whirlwind of decisions I had to make in just a couple of hours to figure out where I’d sleep that night.

As I lay down, I felt a burning sensation on my hip, right where my backpack strap rests.

Hip injury caused by my pack strap

The wound didn’t look great—it was red, swollen, and oozing yellow fluid with a strong smell. I removed all my protective dressings, cleaned the area with iodine, and sat down to meditate.

Healing through meditation

Meditation became a powerful tool for me when I was recovering from my knee injury. As I shared in My Broken Tower Joe Dispenza’s book introduced me to the practice, and I truly believe it helped me recover in just three months when doctors had estimated at least six.

With my mind racing from the day, I focused on my breath, let go of all the overstimulation, and concentrated on the pain in my hip. I visualized how it felt while walking, how the strap rubbed against it.

Then I shifted into positive thoughts—envisioning the wound healing, and imagining my backpack sitting comfortably without causing pain. In that moment of deep calm, I closed my eyes and drifted off to sleep.

Breakfast with Salty Chef

I woke up early, before anyone else in the campground. Some folks in their camper vans were just starting to stir, but my friends were still fast asleep. I headed to the local grocery store to do a light resupply—I already had enough food for a day in Yosemite and the stretch to Kennedy Meadows North.

The store was nearly empty, and prices were sky-high. I bought a few snacks and a carton of eggs—Salty Chef had mentioned he was craving some. I returned to camp just as everyone was starting to wake up.

Salty Chef doing his magic

Salty Chef took the eggs and got to work on breakfast.

Differents goals

While organizing my pack, I chatted with him about how he was doing and what his plans were. I hadn’t wanted to ask before, but I had noticed that Coyote, Mufasa, and Simba were no longer with the group. Now that things had calmed down, I finally brought it up. He told me:

– Yeah, it’s kind of my fault, Roadrunner. After Bishop Pass, I got tired of us being such a big group. We really need to pick up the pace—we’re behind schedule. So our goals just weren’t lining up anymore. I told them we had to move faster. We stayed together a bit longer, but ended up parting ways after taking Piute Pass again.

And then he added:

– I’m feeling better now. I had lost some of the joy—was too worried about the group, and our pace was all over the place. I wasn’t confident we could speed up. Honestly, we may even have to separate from Saida and Jumper too. We have even less time than they do to finish the PCT.

Mindblow

At that moment, my brain lit up with internal alarms. I could barely focus on what he was saying. He was already talking about finishing the PCT.

In my head, I knew I’d come a long way, but I’d never really let myself think of it as a realistic goal—to actually make it to Canada. But hearing him talk about it flipped a switch. It hit me: I’m doing great on the trail. And if I keep going like this… I can make it.

It’s okay to take different paths

– Salty Chef, I said,

– there’s no one right way to hike the PCT. We’re all out here doing our best. This isn’t a guided tour—it’s your own journey. And if you find people to share it with, that’s beautiful. But if paths diverge, that’s just life. We all experience this in our own way. Don’t put it all on your shoulders—just enjoy this adventure with your son.

He smiled at me. He said he was grateful we’d met and hoped we could keep hiking together down the line. He told me their plan was to take a zero day and return to the trail the next afternoon. They might even have a cookout. But he also said he wasn’t going to Yosemite Valley after all.

I told him I was planning to do laundry and then try hitching a ride to Yosemite. I had to try—I was so close.

He smiled again and said, -I’m sure we’ll meet again on the trail, my friend.

Laundry time

Lee Vining RV campgrond

At the RV camp, there was a laundry room—probably the only one in all of Lee Vining—because it was clearly the busiest spot in the whole campground. Jumper and I gathered our dirty clothes and headed over.

I found an open machine, and since it had a huge capacity, I threw in Jumper’s clothes along with mine and started the wash. We stepped outside to sit in the sun and wait for it to finish.

Just as we were walking out, I realized I hadn’t added detergent. I ran back in, found the soap vending machines, and dropped my coins into the slot. These machines were old-school—you insert coins, give it a good smack, and if the soap gets stuck, a “gentle tap” usually does the trick.

That’s exactly what happened. I gave it a quick knock, grabbed the little cardboard box that dropped out, opened the washer, and dumped the soap into the swirling pile of wet trail clothes.

Jumper Making Friends

When I got back outside, Jumper was chatting away energetically with two women. The speed and rhythm of the conversation caught my attention—it wasn’t in English.

I sat down on the ground nearby. Jumper noticed me and said:

–Have you met Diego? Or Roadrunner! He’s from Uruguay and a good friend of ours.

The women looked familiar, and then it clicked—they were PCT hikers too. I’d seen them before.

–Hey! I remember you from the trail.

–Hi, Roadrunner! Yeah, we’ve crossed paths before. The first time was way back in the desert—you told us how far we had left to hike. We thought we’d never see you again because you were going so fast.

I laughed and said, “Well, here we are—at the end of the Sierra!”

The “Austrian Sisters”

At that moment, I clearly remembered where I’d seen them before. It was during those early desert days. I had been hiking solo, obsessively sticking to my schedule, trying to adjust to this new way of life.

The “austrian sisters” at the Sierra (ph: @mitterbergers.on.trail)

Flashback: Learning Curve

Back then, I was deep in my head—focused, introverted, a little antisocial. I wasn’t really stopping to chat with other hikers.

Flashback: That Day

I saw the two of them ahead in a lush green valley—a rare oasis in the desert. The trail climbed beside a dusty road, winding toward the horizon. I kept catching glimpses of them—first disappearing around a bend, then reappearing above me on a switchback.

They hiked close together, wore the same shorts, same haircut. They looked like a pro team on a mission.

Flashback: Getting Close

My competitive brain whispered, “Nice, you’re catching up to the pro team.” Then another voice said, “Ugh, if I catch up, I’ll have to talk.”

That’s how introverted I was. But then I spotted a group of hikers stopped by a log, chatting and taking photos. The Austrian hikers stopped to join them.

Boom—this was my moment! I sped up, snuck past, waved politely from a distance, and kept moving.

Flashback: Paths Cross Again

I kept hiking at a steady pace for about an hour, until I decided to take a quick break on a fallen log.

As I took a sip of water, a voice startled me so much I almost spit it out:

– Hey!

It was the same girl who was now sitting right in front of me.

Back to the Present

Now here we were again, months later, reunited in this random little town called Lee Vining.

– Yeah, I remember, I said. It was in that green grove in the desert.

They laughed.

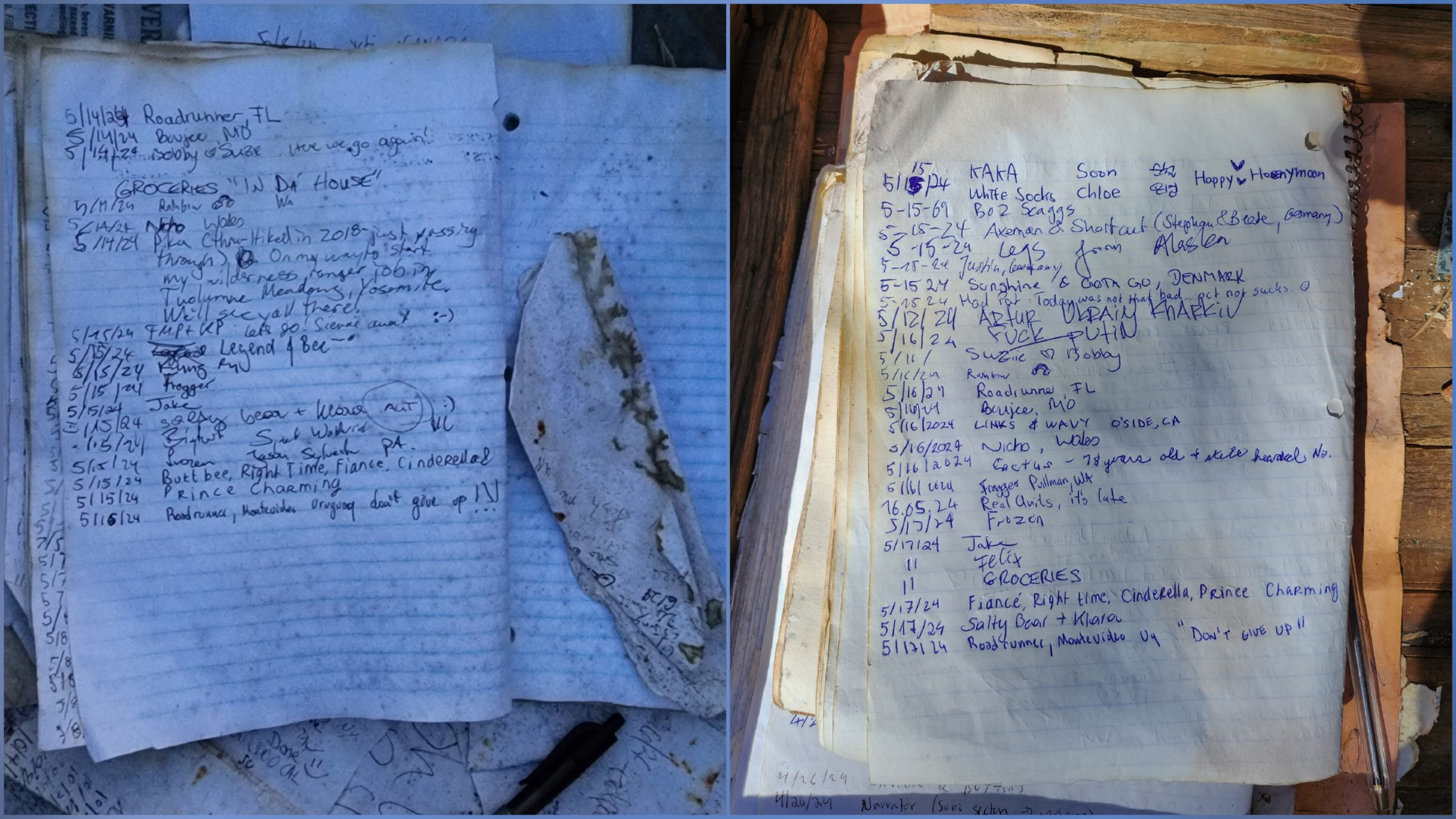

– We remembered your name because we saw another Roadrunner in a trail register, but we knew it wasn’t the same one from Germany.

Then I said,

– Seems like Roadrunner is a popular name out here. I love it, What are your names?

The taller one said, “I’m Salty Bear, and she’s 2 Miles.”

– Wow, great names! I’ve definitely seen Salty in the trail registers.

Flashback to trail registers with the austrian girls

– We’re from Austria! Nice to meet you again, Roadrunner.

– The pleasure’s mine. I was kind of a hermit when we first met, but I’ve loosened up a bit now. Taking things slower.

In the Tough Part of the Journey

Salty Bear and Roadrunner talking

– You’re telling me, said Salty Bear. 2 Miles and I were just talking about how this section is really wearing us down.

– Wait, I asked, did you say friend? Not sisters?

Salty Bear laughed. “Everyone thinks we’re related, but no—we’ve known each other for years, but we’re not family.”

2 Miles added, “We just love our matching shorts.”

We all laughed.

Fatigue and Perspective

– So the Sierra’s been tough for you too?” I asked. “I’m worn out. I dream of dry socks. But when I look up and see where I am, it all feels worth it.

– Yeah, it’s tough, said 2 Miles, but the endless views, the morning coffee, and the town stops make the pain worth it. I actually feel pretty good today.

Doubt and Distance

Salty Bear grew more serious.

– Sometimes I question if it’s all worth it—being so far from our families, our boyfriends, quitting my job, spending my savings. I’m glad I have 2 Miles, but time’s ticking, and we feel pressure to hike faster if we want to make it to Canada. We took our time early on, hiking with our partners, but now we feel the need to push hard.

This Is Life—and It’s Not Easy

I listened quietly, then said:

– Salty, I totally get it. Being an international hiker adds a layer of complexity. We can’t just go home during a snowstorm, or attend a friend’s wedding, or celebrate birthdays with our loved ones. This life is completely different from what we’re used to. Routines change, goals change—and we change too. What you’re doing is not easy. Just look at all the people who started and how few are still here.

I paused.

– You’ve got your lifelong friend 2 Miles—and some random hermit you met in the desert—now sitting across from you in this tiny town. The only people who truly get what we’re living through are right here. The ones who wake up with frozen toes and still manage to smile while eating candy atop a snowy pass with jaw-dropping views.

I finished:

– Very few people make it to this point on the PCT. That means what you’re doing is amazing, and you should be proud of everything you’ve accomplished. This is life!

A Genuine Connection

We kept chatting about our families, our jobs, everything we’d left behind. The mood shifted. Our energy lifted. Real joy returned.

2 Miles said, “Tomorrow’s Salty Bear’s birthday. We’d love to celebrate somehow.”

That’s when Jumper had a great idea:

– We’re taking a zero here. Why don’t we have a BBQ tonight to celebrate?

Salty Bear lit up.

– Yes, that sounds amazing! Let’s get a bottle of wine or something at the grocery store.

Paths That Cross

I loved the idea—the bonding, the connection, this beautiful moment. But I had a different plan.

For me, Yosemite Valley was a pillar of this trip. I’d dreamed of visiting since Day One, told everyone back home it was part of my journey—including my dear Chilean friend, Coyote.

So I decided to move on. I packed up and headed out toward Yosemite. I’d miss this incredible BBQ, but after such a meaningful conversation, I knew I had solid friendships on the trail.

And as the PCT has taught me time and again—if the trail provides, maybe I’ll hike with them again someday.

On My Way to Yosemite Valley

I said goodbye to all my friends. Part of me was screaming to just stay and chill on the green grass of the RV camp instead of walking 5 kilometers down the road, trying to hitch a ride to Yosemite Valley—especially considering the road had only opened the day before.

Hitting the road

I had a feeling hitching a ride wouldn’t be easy for several reasons:

- There wasn’t a lot of traffic heading up toward Tioga Pass, and I needed someone who was actually going all the way to Yosemite Valley, which was much further.

- This wasn’t a typical spot for PCT hikers, so there weren’t well-known places to thumb a ride.

- Yosemite is a tourist destination, and most people heading there had their cars packed to the brim. Picking up a hiker with a huge backpack wasn’t exactly ideal.

When I got to the intersection, to my surprise, a lot of cars were indeed taking the turnoff toward Yosemite Valley. That was exactly what I needed. I found a pullout just a bit up the road and positioned myself in a spot where I could wave at cars coming from both directions.

My hitchhiking spot

Heavy Traffic

I set my pack down and stuck out my thumb with passion, hoping to catch someone’s attention. Two hours went by—nothing. Some drivers gave me a quick wave that meant “good luck,” to which I responded with a big smile. I started thinking that if I could at least make it to Tioga Pass, it would still be helpful. From there, I could potentially reconnect with the PCT if no one was heading to Yosemite Valley.

Huge RVs kept rolling past me. I had a hunch they were Yosemite-bound, packed to the roof and sometimes even towing a smaller car to drive around once inside the park.

Happy hitch

After 30 more minutes, I decided to move farther up the road. Maybe the drivers couldn’t see me in time due to the curve ahead. As I was walking, a car coming from the opposite direction rolled down the window and asked:

— Where are you headed, backpacker?

— My final destination is Yosemite Valley, but I’d be happy with Tuolumne Meadows or Tioga Pass too.

— Alright, we can take you to Yosemite Valley if you help us clear a bit of space in the back seat.

I couldn’t hide my smile! The car made a U-turn and pulled over in front of me. We rearranged some stuff in the trunk, and I jumped in.

My Roadside Saviors

There were two people in the car, a guy and a girl, both probably around 25 years old.

My ride to Yosemite Valley

They told me they were heading to Yosemite Valley without much of a plan. The guy had been there countless times to climb all around the valley. It was one of his favorite places in the U.S.—there were tons of climbing options, and it wasn’t hard to find little-known spots to explore in solitude.

For her, it wasn’t exactly her first time, but it seemed like it was her first trip like this with him. She was super excited to hear his stories and explore with him.

We shared our experiences. They were shocked that I was hiking the PCT and even started wondering if they could do something like it themselves. They both lived in the city, and ever since they’d gotten into climbing, they jumped at any chance to hit the road and go explore.

The drive to Yosemite Valley was long. We shared laughs, tunnels, and endless views of towering granite peaks stretching across the horizon. Once we took the junction to Big Oak Flat Road, the traffic was wild.

We were literally driving in a line of vehicles, all heading toward the park. That road came from the opposite side of the mountain range I’d crossed on the PCT. It was clearly the busier access point—understandable, since Tioga Pass had only just reopened.

My new friends dropped me off near Curry Village. They told me to head to the ranger station, where I’d be directed to the Yosemite Valley Backpackers Campground. For just 10 bucks, I could spend the night there. That sounded amazing!

I thanked them and kept walking. I had made it—I was finally in Yosemite Valley.

Yosemite Valley

I had finally made it into the park. I went to the ranger station and was warmly welcomed. They told me I could stay at the Backpackers Campground for one night without any issue. I had never received such a friendly welcome, especially considering it was past 4 p.m. and everything was about to close.

My plan for the day was simple: set up my tent and explore as much as I could before sunset. Then I’d head to the main area of the park and figure out what to do the next day. I had no reservation, so hiking Half Dome seemed out of the question—even though my friend Romi had begged me to try no matter what.

Valley Loop Trail

Leaving the camp, I picked up the Valley Loop Trail. It circles the entire valley for about 33 kilometers. It was already 5 p.m., so a full loop was out of reach, but I could walk a portion and end up near the central part of the park. The trail was easy and very accessible. I came across lots of families enjoying the same path.

All along the trail, signs explained the history and culture of the land’s original inhabitants.

Forests, trees, and endless granite walls

The geological variety was stunning. From the dense woods, I could see towering walls of polished granite. It felt deeply spiritual.

The most well-known native people here were the Ahwahneechee. For them, these landscapes held deep spiritual and practical meaning. The valley was known as Ahwahnee, meaning “the open mouth,” describing the valley’s long, narrow shape and towering granite walls rising abruptly from the forested floor.

Mirror Lake

After about 15 minutes, the trees began to open up, letting light pour in. A few more steps and there it was: Mirror Lake.

Mirror Lake with Mt. Watkins in the background

It didn’t seem like a year-round lake. It was likely full now due to snowmelt, but the water was shallow and patches of grass emerged from it. This meant it might dry up in a few weeks.

But the real magic was in the reflection—Ahwiyah Point and Half Dome mirrored perfectly on the surface. It was a moment that brought stillness to the soul. These were the kinds of views that make you reflect not just on yourself but on the lives of those who lived here long ago.

Mirror Lake and the reflection of Ahwiyah Point

Coexistence

What must those ancient eyes have seen? So many interpretations, so many truths. I often wonder how they understood these places, how they felt their power. Sadly, we weren’t able to live in harmony with them, let alone with other forms of life. If we can’t even respect our own species, how can we expect to protect the homes of the animals and plants that lived here first?

That’s where Leave No Trace comes in. It acknowledges we can’t have zero impact, but it pushes us to minimize our footprint so these places can remain untouched by commercial exploitation. I see it as a fair compromise.

The moon watching over Half Dome

Presence

More than anything, this place invites presence. You sit down and let your eyes take you places your feet can’t. What does that tree see with Half Dome behind it? You try spotting people climbing the summit, but it’s so massive, humans disappear into the scale. You imagine the view from the moon itself.

I continued along Tenaya Creek, exploring stunning viewpoints at every turn. Eventually, I saw a sign for the John Muir Trail. That’s when it hit me—what a beautiful way to end the JMT: walking into Yosemite Valley on foot. The granite cliffs can’t be seen from the trail above; they reveal themselves only once you descend into the valley.

In the shadows of the Dome

A steady stream of people were hiking in, most with small daypacks, not typical for JMT hikers. My curiosity got the better of me.

–Hey, are you finishing the JMT? I asked a girl walking by.

She laughed. No way! My friend did it last year. She’s crazy! We just came down from Half Dome. Started at 9 a.m., and we’re only getting back now. It was harder than I thought, but so worth it.

Then it all made sense. Most of the hikers I’d seen were actually coming down from Half Dome.

–Wow, that must have been amazing. I’m hiking the PCT and just arrived in the valley. I’m staying the night but don’t have a permit for Half Dome. I guess I’ll settle for seeing its shadow.

She looked shocked. WHAT?! You’re walking from Mexico? Go to the ranger station! I’m sure they’ll give you a permit. With your PCT pass, you can probably do anything.

PCT superpowers

I laughed. People really believed the PCT permit was a golden ticket. In truth, it’s a powerful document, but still pretty regulated. And this was Yosemite, one of the crown jewels of U.S. national parks. My “superpowers” didn’t stretch that far.

I thanked them and headed toward Curry Village. There were restaurants there, and I was hungry enough to celebrate.

Curry Village

Even after seeing all those people on the trail, nothing compared to the crowd in Curry Village.

I found a spot selling burritos for $10, grabbed one and a couple of beers, and sat down. Then I heard it:

–Hey Roadrunner! HOW ARE YOU? SO MUCH TIME!

I turned, and I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was Lennette and Alice! I hadn’t seen them in over a month, since Agua Dulce.

–I can’t believe it! We’re meeting here!

–Come on, we’ve got a table with a bunch of PCT hikers. Join us!

More than ten hikers were gathered, packs scattered everywhere, beers in hand, celebrating. We had made it through the toughest part of the Sierra. It made sense to rejoice.

Celebrating with old friends

We caught up. Lennette and Alice were now hiking with a big group. They split up into smaller pairs but coordinated resupply points. Jesus, Sunscream, and many others were part of it.

I felt at home, surrounded by my trail family in one of the most beautiful places on Earth. I ran to the store and bought an 8-pack of beer. The night was full of laughter and joy. It felt like I’d known these souls forever.

Lennette told me she was planning to climb Half Dome tomorrow. Alice was going to rest instead. They would hitchhike back to the trail afterward.

I asked how Lennette planned to get a permit.

–A lot of people go to the ranger station really early. I don’t think I’ll do that, though. I want to enjoy the morning here.

My decision

Talking to her, remembering my chat with Coyote, I made up my mind: I was going to try. I would wake up at dawn, go to the ranger station, and see if I could get a permit. I wanted to see the shadows of Half Dome—this time, from the top.

Over the Shadow of the Dome

I woke up early in the morning, packed up all my gear, and prepared a small daypack for a hike. I left the rest of my belongings secured inside the bear box. My destination was the Wilderness Center, located east of my spot, in an area known as Yosemite Village.

I followed part of the Valley Loop Trail and after a few steps into the woods, I reached a wide bike path that offered an incredibly open view of the valley. As this scene unfolded before my eyes, I spotted a stunning waterfall crashing violently near the area I was heading to.

Upper Yosemite Falls

Bike path and view of Upper Yosemite Falls

A memory came rushing in as I stared at that view. While walking, I watched the powerful waterfall rush down a vertical granite wall that must have been at least 500 meters tall. The sound of the water mixed with the early rays of sunlight triggered an image I had stored in my mind. I remembered this place—this waterfall—turning into a glowing ribbon of fire in the evening light.

As I walked toward it, I kept watching the cascade, but slowly realized this probably wasn’t the exact waterfall I had in mind. Mainly because this one had a much stronger flow and a wider drop than I remembered. Sure, the intense flow might have been due to peak snowmelt season, with all the water from the Sierra Nevada mountains feeding into it. But the shape of the mouth was definitely wider.

When I reached the base, I found a plaque explaining the story of Upper Yosemite Falls. The Ahwahneechee people called it Cholock, and believed it was home to a powerful spirit—a guardian of the waters. The force of the waterfall was viewed with awe and fear. They said approaching it without proper respect could bring spiritual or even physical consequences.

After seeing its power and hearing its roar, I understood exactly why the native people felt that way. It was intimidating—even from a distance, and surrounded by civilization.

Park Ranger Experience

I arrived at the Wilderness Center just as a park ranger was giving her Leave No Trace talk and explaining what to do in case of a bear encounter. The clarity in her words, the passion in her delivery—it really caught everyone’s attention. You could tell they were professionals, and that their training was spot-on. They had clearly crafted their message with care, to make sure it landed with all types of visitors.

I found their ability to communicate both inspiring and effective. That, in my opinion, is how you encourage people to truly care for the natural spaces they’re stepping into.

Then she had us form separate lines—one for day hikers, one for those with Half Dome permits, and one for those without. At that moment, she made it very clear:

– We are not issuing any day-use permits for Half Dome today.

That felt like a bucket of cold water. Still, I stepped forward and explained that I was a PCT hiker hoping to climb Half Dome. She looked at me, paused for a second, and then said:

– Listen, I might have a solution for you. What we can offer is a permit that covers the section of the John Muir Trail between Tuolumne Meadows and the park. We’ll also include a Half Dome permit as part of the route. Since you’re a PCT hiker, we trust that you can cover the distance and exit the park the same day. This wouldn’t apply to most people, who usually need an overnight stay to recover before hiking out.

Me with my Half Dome permit

I thanked her, over the moon, and walked away wagging my metaphorical tail like a happy dog. I took my permit and headed straight for the trailhead—just in case they changed their minds.

Mist Trail

I headed to the area known as Happy Isles, at the far eastern edge of Yosemite Valley, where the trailhead for the Mist Trail begins.

The path started with a steep incline, but it was wide and extremely well-maintained—like walking up a highway. People were stopping every 100 meters to catch their breath. Meanwhile, with my full-on hiker legs, I was moving at a pace way beyond average. That’s when I realized how much my body had changed after hiking the PCT. Everyone around me looked like they were moving in slow motion, gasping for air while I climbed effortlessly.

“Happy” hiker on trail

To my right, the Merced River accompanied me the whole time. I was climbing up the edge of a canyon where, down below, a wild and relentless current roared.

Just a few minutes into the hike, the trail opened up a bit—and then I understood why it’s called the Mist Trail.

Mist from Vernal Falls at Mist Trail

The entire trail was soaked from a fine mist constantly falling over the area. You could tell this wasn’t occasional—it was permanent, created by the massive waterfall just ahead. How did I know? Because of the thick green moss growing between the rocks, like nature’s carpet. It made the hard, wet granite surfaces feel oddly soft.

Multicolor Show

As I climbed those stone steps, I was hit with a view that will forever be imprinted in my memory: Vernal Falls and an unexpected multicolored visitor.

Rainbow over Vernal Falls

I paused for a moment to take in this breathtaking sight. I imagined the rainbow only appeared when the sun pierced the canyon at just the right angle. The air was thick with mist—tiny water particles floating everywhere—creating the perfect conditions for this dreamy spectacle. As I continued climbing, rainbows kept appearing from different angles, offering new perspectives in a fairytale landscape.

Full rainbow above the trail

People were going up and down, all in awe of the view. We were walking through mist, surrounded by pure vegetation growing out of cracks in the rock, and a perfect waterfall flowing straight down a sheer granite wall.

Vernal Falls

Taking a photo of the falls meant getting soaked. At one point, I gave in—found shelter behind a boulder, pulled out my camera, and took the shot.

Vernal Falls

What I captured wasn’t a technically perfect photo—but it reflected what I was feeling in that moment: drenched, inside the fog, and standing just a few meters from a thunderous natural wonder. Every time I look at that image, I hear the relentless sound of water pounding against the rocks.

From there, the trail cuts into the canyon wall—man-made—and leads you to the top of the falls. That’s where you can stand in the exact spot where the water takes its leap into the void. Before it falls, the water gathers in a huge natural pool, much wider than the drop itself. This place is called the Emerald Pool.

Top of Vernal Falls

Nevada Falls

After a short break, I continued climbing through this incredible canyon. It’s wild how, after just a few turns, the sound of falling water suddenly disappears. And just like that, most of the people were gone too.

Canyon View

Most hikers seemed to stop at the Emerald Pool to rest—or maybe that was their turnaround point. Others may have simply underestimated the climb and decided not to push any further.

For me, it was a blessing—the trail was much quieter from here on.

Eventually, I began to hear the familiar roar of water once again. After a few more turns, Nevada Falls suddenly came into view on my right. This waterfall was twice the height of Vernal Falls.

Nevada Falls

It looked like a giant granite slide, where the water glided down at crazy speeds. Unlike Vernal, this one didn’t create constant mist, probably because it was channeled more tightly into the rock.

After the falls, the trail kept going up—but with a gentler slope.

Crossing Paths

I entered a massive forest, where water trickled everywhere, and tall trees painted the surroundings in shades of green, brown, and orange. Eventually, I reached a sign for the Half Dome Trail and turned to continue my climb.

Junction between the JMT and Half Dome Trail

That’s when I ran into Lennette, walking down in the opposite direction.

-Hey Roadrunner! I’m coming down from the summit—you’re going to love it. The final section with the cables is absolutely insane!

-Lennette! So good to see you. I’m so excited—this trail is incredible. Is it crowded at the top?

-Yeah, when I got there, I was the only one. But now there’s actually a little line forming to get onto the cables. I suggest grabbing a pair of gloves for the climb—the wire can really hurt your hands.

-Thanks so much, my friend. I’m sure we’ll see each other again on this journey. Our paths have crossed so many times already. Maybe we’ll end up hiking together.

She smiled and said:

-I’d love to hike with you again.

We hugged, and once again, our paths crossed—just for a moment—before continuing on.

Half Dome

After saying goodbye, the trail steepened significantly—and suddenly the giant slab of granite came into full view.

I got closer and could make out what looked like a black line running up the side. At first, I wasn’t sure what I was seeing, but then it clicked—those tiny dots were people, slowly making their way up the summit.

Tiny ants climbing the rock

At the base, many hikers were resting and preparing for the brutal climb ahead.

Roadrunner at Half Dome

The Ascent

I sat down to observe how others were doing it. People who were coming down would approach a rock wall and leave gloves behind. Apparently, someone had left several pairs there for others to use on the climb.

I grabbed a pair and started the ascent.

Climbing Half Dome

At first, it seemed manageable—I barely needed to grip the cables. But that changed quickly. It became impossible to stand without holding tightly to the metal lines.

Everyone was hugging the cables, not just to let others pass, but because they were completely exhausted. Gripping the rope was the only way to give their legs and forearms a break.

In my case, the PCT had taught me a valuable lesson:

If you want to go farther, you need to go slower.

My Father’s Memory

That’s when I remembered something about my dad. At work, people used to call him: “The black chief—no rush, no pause.”

And it was true. He was unstoppable—always doing something, always moving. But never stressed. He took his time and did things with care and purpose.

He didn’t rush—but he never stopped either. He did things with love, with focus. I see that part of him in me—especially when I face a big challenge. I don’t let the effort weigh me down. I enjoy it.

I don’t wait to celebrate at the summit. I celebrate every single step.

And so, it was—

Step by step,

Breath by breath,

Smile by smile—

View at the top of the Half Dome cables

Over the Shadows of the Dome

That’s how I reached the summit of Half Dome. I was standing on top of one of the most iconic mountains in Yosemite National Park.

Roadrunner on top the Half Dome

From up there, I could see far below the valley where I had started my day. The buildings looked tiny, and vehicles were nothing more than tiny specks on the ground—probably only visible because of the way they reflected the sunlight now reaching the valley floor.

Hiker legs

I checked my altimeter: 2,680 meters (8,800 feet) above sea level. The valley lay 1,400 meters below. Just four hours earlier, I’d been down there getting my permit. This stat alone shows how much stronger my body had become.

Let me explain. In mountaineering, there’s a common rule of thumb for estimating vertical ascents in mountain ranges below 4,000 meters: the average pace is about 200 meters of elevation gain per hour. In this case, I’d climbed 350 meters per hour—that’s 75% faster than average.

That’s why I had passed absolutely everyone on the trail. And I don’t say this as a brag—just as a confirmation of what happens to the human body when we do something regularly and naturally. This is what happens to PCT hikers. It’s what we call hiker legs.

Culture

To the Ahwahneechee, the Native people of this land, this mountain was known as Tis-sa-ack, a name tied to an ancestral legend.

Tis-sa-ack was a powerful woman who traveled to Yosemite Valley with her husband. During a heated argument, she furiously spilled the water from her basket. That water was so powerful it carved out the valley. Curiously, the current scientific explanation says something quite similar—these valleys were formed by glacial movement, later deepened by the relentless erosion of mountain water.

The only difference is that science removes the mythic flair and personification that Native stories give to nature. Personally, I believe in the scientific version, but their perspective was remarkably close. I use the word “believe” deliberately—because that’s exactly what science is for me here: a belief rooted in human observation. I wasn’t there, and neither were the scientists. So I won’t use that knowledge to discredit the epic and beautiful beliefs of another culture.

The valley shaped by Tis-sa-ack’s fury

According to the legend, as punishment, the gods turned both Tis-sa-ack and her husband into stone: Tis-sa-ack became Half Dome, and Nangas, her husband, became North Dome, across the valley.

Geology

As I’ve been sharing throughout my journey in this region, the dominant rock here is granite, specifically a type known as granodiorite. These formations were part of a massive igneous rock body that solidified underground around 100 million years ago, during the Cretaceous period.

Although today’s name, Half Dome, refers to its shape—as if a dome were cut in half—this was not the result of a single event. Instead, it took several geological stages to sculpt what we see now. The exposed granite layers underwent exfoliation, caused by expansion and pressure, which led to rock shearing and flaking. Later, glaciers carved through the emerging valley, polishing and slicing the giant dome as they slid past—giving it that iconic clean-cut look, like a knife had sliced it in half.

Elevation

Even though Half Dome is world-famous, it’s not the highest peak in Yosemite National Park. That title belongs to a mountain I passed on my left while hiking the PCT—a peak you might remember from my earlier posts: Mount Lyell. It rises to 4,000 meters (13,100 feet) and is the tallest mountain in the park.

Closing Thoughts

This moment was deeply emotional for me. I had finally reached one of the places I dreamed of visiting in the United States. I still have more dream destinations ahead in this journey, and I hope I’ll have the strength to walk to them as well.

More importantly, the Sierra and the PCT have sculpted something new within me. They’ve moved and shaped a different version of who I am. I feel whole, open to the world, and ready to embrace whatever comes next. I hope this feeling stays with me, and I look forward to continuing to share with all of you just how magical it is to walk through the adventure of your life.

Thank you for being here. See you in the next chapter—

The final steps through the Sierra Nevada are approaching.