Bruce Benjamin stands by a Pitkin County Sheriff’s patrol vehicle — an AMC Eagle — in a photo taken in the late 1980s. He began his tenure with the department in 1983, joining the force to help open a new jail and train its deputies. Over the years, Benjamin served under four voter-elected sheriffs in a career where his primary focus was investigating crime involving juveniles. A 1981 graduate of the University of Colorado, he launched his law enforcement career with the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office, where he worked for two years before relocating to Aspen. There, he joined the team under Sheriff Dick Kienast, widely recognized for his progressive, community-oriented approach to policing.

A Massachusetts state trooper who was the subject of Norman Rockwell’s “The Runaway” once said of the iconic painting, “Wherever you go, in state police agencies or law enforcement agencies, you’ll find a picture of ‘The Runaway’ hanging somewhere.”

Until Friday, you could find the framed print hanging on the wall of Bruce Benjamin’s office at the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office on Aspen’s East Main Street. To Benjamin, “The Runaway” encapsulates his approach to juvenile police work: protection, compassion, and connection before punishment.

The 66-year-old investigator retired on Friday after a 42-year career with the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office, where he served under four voter-elected, progressive-minded sheriffs — Dick Kienast, Bob Braudis, Joe DiSalvo and now Michael Buglione.

His main focus was investigating cases involving juveniles. In total, Benjamin spent close to 45 years in law enforcement, starting with a two-year stint at the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office.

“It’s the greatest, most meaningful career you could have — where you can make a big difference in people’s lives,” Benjamin said Wednesday from his office — a modest and utilitarian place for case files, investigative materials and a few personal effects. “You don’t make enough to get rich in law enforcement, but you make enough to live with the benefits and health insurance and that type of thing. But it is the most meaningful work you can do.”

Bruce Benjamin is retiring after 41 years with the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office, where he wore many hats but specialized in juvenile crimes. Benjamin, whose last day with the organization was Friday, said the Norman Rockwell painting “The Runaway,” which hung in his office, resonated with him because of its theme of compassion and connection.

Over the years, Benjamin led investigations into such crimes committed by juveniles as vandalism, theft, and sexual assault. He would cite underage kids for drinking or taking illegal drugs, from backwoods keg parties to Winter X Games shenanigans.

He investigated crimes committed against juveniles also — cases of child exploitation, child pornography, child abuse, sexual abuse.

The personal reward of helping others gave deep meaning to his work — whether it was gathering evidence that led to the conviction of a child abuser, guiding a troubled juvenile onto a better path, or removing a young person from a dangerous home environment. Sometimes, Benjamin’s impact came simply from being present — not to fix everything, but to listen, to show up and to let someone know they weren’t alone.

Benjamin’s job also meant witnessing tragedy firsthand — making heartbreaking calls and in-person visits to families of those who died unexpectedly, sifting through mountains of paperwork and digital evidence, and answering emergency calls in the dead of night. Unlike big-city police work, where officers often don’t know the victims or their families, law enforcement in small, rural Pitkin County is far more personal because of the local ties and connections.

Now, he’s ready to step away.

“It takes its toll,” he said. “Even I, who had been pretty resilient, got worn down by the kinds of cases I handled — especially when I was on call on weekends. I’d be the one responding to suicides, handling those scenes, writing the reports. The dead bodies, the trauma … it all adds up. I’m looking forward to not seeing those kinds of things anymore. It’ll take a little time to decompress.”

He added: “The other thing I’m looking forward to is not having my phone ring at night. Between juvenile cases and being on call for general investigations, that phone was always ringing.”

This Aspen Times front-page photo published May 3, 1984, shows a young Pitkin County Deputy Bruce Benjamin escorting Keith Porter from the jail to the courthouse. Porter was convicted in March 1986 of second-degree murder in the shooting death of Aspenite Michael Hernstadt. Benjamin’s last day with the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office was on Friday, following a local career in law enforcement that began when he was hired in 1983 to help get the new jail operating properly.

While much of his caseload focused on the county’s youth, Benjamin also played key roles in major adult cases — ranging from rare homicides to more frequent sexual assaults — as well as traffic fatalities, physical assaults, plane crashes, mountain deaths and suicides.

He helped provide security detail for First Lady Michelle Obama on her frequent Aspen vacations, or more recently when vice president-elect J.D. Vance and his family hit the slopes for the winter holidays.

“Think about that,” said Pitkin County Sheriff Michael Buglione. “Forty-two ‘f—ing years,” praising Benjamin’s time “served with consistency, compassion, dignity and respect.”

Benjamin grew up in Manhattan, New York, earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado, and started his law enforcement career in Boulder before his long haul in Pitkin County.

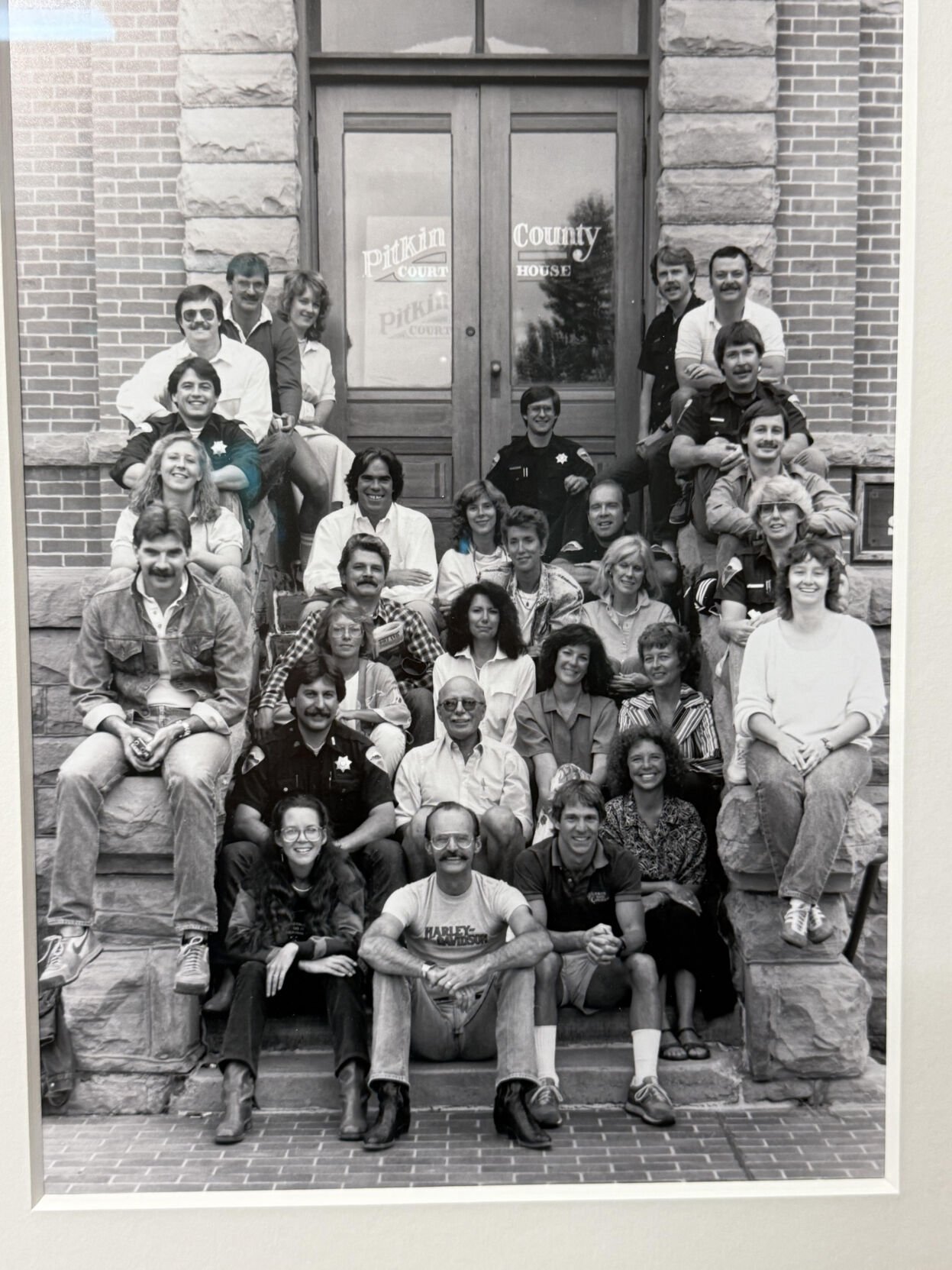

On Wednesday on the westside entrance of the courthouse, sheriff’s office employees gathered for a photograph shoot some 40 years ago after Benjamin was in the same spot for a photo shoot in 1985. Other than the western entrance shown in both photographs, there is another common denominator: Benjamin.

In his remarks to those gathered around for the shoot, statements which Buglione shared with a reporter after the event, the sheriff said, “Bruce is not the kind of man who’s ever needed the spotlight. He doesn’t just talk to hear himself speak. When Bruce says something, it’s because it matters. And it’s what made him such an effective investigator: He’s methodical, observant, unshakably calm under pressure. He has that rare quality that can’t be trained or taught. He listens. He truly listens. He listens to his victims, the witnesses, he listens to the evidence and his intuition.”

When Bruce Benjamin, right, joined the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office in 1983, “swatting” crimes, which is when a prank call is made to generate a large emergency response, were unheard of. Following a swatting incident in February 2022 that shut down public schools valleywide, as the local incident commander, Benjamin, far right, joined Aspen School District’s superintendent then, David Baugh, and Pitkin County Undersheriff Alex Burchetta to address the public about their concerns.

From NYC to the Rockies

Benjamin moved west for college, drawn to the mountains and outdoor lifestyle. He had previously visited Colorado and liked what he saw and experienced.

“I grew up in New York City and did not like the city life at all,” he said. “So I thought Boulder back in the ‘70s when I moved there would be just idyllic, and it was.”

In college, he was active in the CU climbing club and joked that he got into law enforcement because “who’s going to pay me to climb mountains.”

In 1983, then-Sheriff Dick Kienast recruited Benjamin to assist with the transition to a county jail facility that would open in January 1984 and where it remains today. The original jail, from the 19th century, was in the basement of the Pitkin County Courthouse, also used by the sheriff’s office back then.

Benjamin liked the idea of relocating to Pitkin County and working under Kienast and Braudis, and playing a role in the new jail operations.

Pitkin County also did community policing, which Benjamin appreciated from his time in Boulder. Back then, community policing was considered a progressive law-enforcement philosophy based on police building strong relationships with the communities they serve.

Bruce Benjamin, juvenile investigator with the Pitkin County Sheriff’s Office, waves to the crowd during Aspen’s most recent Fourth of July parade. Benjamin is riding off into the Hawaiian sunset for retirement: His last day on the job, after 41 years in Pitkin County law enforcement, was Friday.

Aspen also was a pretty cool place to be back then, Buglione recalled. When Benjamin was being recruited, he asked one of the jail administrators what it would be like to work in Pitkin County. Buglione recalled the response was something like: “‘It’s amazing. We’re up in the mountains, we wear blue jeans, we are laid back and it’s so cool.’ That’s what made Bruce come out to Aspen 42 years ago.”

The Kienast and Braudis philosophies toward community policing were not universally received in Pitkin County but not enough to hurt them with voters, neither one losing, or coming close to losing, at the polls.

Kienast and Braudis didn’t allow undercover work by their deputies, arguing the method of policework infringed on people’s rights and created potential for a violent encounter. Kienast and Braudis, as well as DiSalvo and Buglione, also operated from a philosophy that people engaged in illegal substance use were better suited for health treatment than incarceration.

“As communities, they (Boulder and Pitkin counties) weren’t completely opposed to each other,” Benjamin said. “The only difference, the biggest difference, was Pitkin was smaller. There were 160 deputies in Boulder to 20 deputies in Pitkin. So the size was a huge difference, and certainly the concept of moving from this cage in the basement (the old Pitkin County Jail) that was built in 1896 and I work down there for seven months, before the new jail was completed, and then moved to a modern jail was a big step for Pitkin, and hiring staff that would be dedicated to the jail.”

This photo was taken in 1985 on the western entrance of the Pitkin County Courthouse where the sheriff’s office’s employees used to work. Bruce Benjamin, third up on the right, is surrounded by an assortment of law-enforcement colleagues, some who still live in the area. Also pictured is the late Sheriff Bob Braudis, smiling and wearing the white oxford. Benjamin worked nearly 25 of his 41 years in Pitkin County under Braudis. The late Dick Keinast, whose progressive law-enforcement philosophy inspired the “Dick Dove and the Deputies of Love” title, hired both Braudis and Benjamin.

After two years where he spent time in both jails, Benjamin joined the sheriff’s office’s patrol division where he worked seven years. It’s the patrol division, Benjamin said, where “you learn everything. Everything. And of course Bob (Braudis, who was elected sheriff in 1986 and remained in that post for nearly 25 years) called me in and asked me to take over the juvenile area of the sheriff’s office.”

Benjamin’s jurisdiction for patrolling and juvenile work was mostly in unincorporated Pitkin County — among them the Fryingpan River valley, the Redstone area, Woody Creek, Starwood, Crystal River, Aspen Village, Lazy Glen and the Aspen-Airport Business Center.

“There is quite a range of socioeconomics, though some people might think that you see rich people every day, but of course that’s of course not the case,” he said.

He noted that “there can be a lot of child abuse in remote rural areas, because people want to move to areas like that where government is not as involved.”

Over the four decades in law enforcement, Benjamin has witnessed sweeping changes in his field, due largely to the rise of technology.

“When I started, we were handwriting reports or using a typewriter,” he said. “The national computer system was basic, and even then, it was down half the time.”

Benjamin said the evolution of forensic science, from DNA to automated fingerprint identification, has dramatically reshaped how crimes are solved. In the past, investigators needed a suspect’s fingerprints to make a comparison, Benjamin said, noting that “you had to have a suspect and get his prints. And then you could compare the two.” These days, prints can be scanned and matched digitally within minutes.

When asked about today’s crime environment versus the one in 1985, Benjamin believes it may have been easier to get away back then, but law enforcement was more reliant on human skills like observation, interrogation and intuition.

“Those of us who started before body cameras and high-tech tools got really good at reading people — their gestures, their mannerisms,” he said. “You had to.”

This recently shot photograph on the western entrance of the Pitkin County Courthouse shows Sheriff Michael Buglione and Juvenile Investigator Bruce Benjamin seated on the front row. At the end of Friday, Benjamin stepped down after a 41-year career with the force. He has retired and plans to move to Hawaii with family.

He sees a generational shift not only in policing but in basic interpersonal skills.

“Younger officers — and even kids — aren’t always as comfortable with face-to-face interaction,” Benjamin said.

Though they did not work for the same agency, Benjamin and Rick Magnuson, an investigator with the Aspen Police Department, their detective work crossed paths.

The two worked together on cases and leaned on each other’s expertise — especially Benjamin’s deep knowledge of juvenile law and sexual offenses.

“If I needed help or advice on a case, Bruce was the first person I’d call,” Magnuson said.

Benjamin walked the walk when it came to community policing, Magnuson said. Benjamin’s fair-minded approach meant he remained “nonjudgmental,” Magnuson said, even when dealing with suspects.

“I’ve never heard him say a bad word about anyone — including the people he’s arrested,” Magnuson said. “He’s a kind man who did a very difficult job, and he did it so well.

“He’s such a great man and a fair and thorough investigator. He’s mentored me. I’ve learned a lot from him. He represents the best in peace officers.”