He had the ability to communicate with God, the angels and one of the most powerful spirits in the voodoo religion.

This is what Won-G Bruny had been texting Lil Mosey for years. Bruny, a music manager who himself had started out as a hip-hop artist, believed he had a special connection with the spiritual realm that would help guide the up-and-coming Mosey’s rap career. In 2021, Bruny took the musician, then 19, to his native Haiti where, deep in the woods, he blessed the young man with what he described as his family power. After Mosey was accused of rape, Bruny urged him to partake in a Haitian rum-bath ritual; when Mosey was acquitted in March 2023, Bruny told him the voodoo gods had taken a hand in the verdict.

Won-G Bruny, left, and Lil Mosey attend the 66th Grammy Awards at Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles, California.

(Johnny Nunez / Getty Images for the Recording Academy)

Bruny soon began urging Mosey to get out of his contract with Interscope Records, the company that signed him in 2017, after the then-16-year old’s debut single went viral. During Mosey’s five-year relationship with Interscope, Bruny believed the would-be star was not compensated fairly by the label.

“I want to express my disappointment on how … Interscope … have treated Mosey. I think it’s disgusting and despicable. You play with my clients career and have caused him mental trama [sic] …,” Bruny wrote in an August 2023 email to two executive vice presidents at Interscope that was viewed by The Times. “Believe me, you’ve never dealt with anyone like me in real life from the spiritual haiti [sic] I am indigenous and have techniques that the eye cannot see. If 48 hours go by and we do not have a release this is going public in a very bad way for you and Interscope. And I will arrive to your office soon as the worst [N-word] you every [sic] met.”

The message was signed: “Worst Nightmare.”

Interscope’s media representatives and the label executives Bruny emailed did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

Angela Thatcher, Mosey’s mother, never had a good feeling about Bruny. After accompanying her son on the trip to Haiti, the early-childhood educator had advised him to be wary of Bruny: “If he’s trying to finesse you,” she said she told him, “please do not fall for it. I think he talks a lot bigger than he actually is.”

“I just want my son away from [Bruny]. I think he’s being controlled and manipulated by this guy who has convinced him that everyone in his life is against him, including his own family.”

— Angela Thatcher, Lil Mosey’s late mother

Big was how Bruny lived. On social media, he portrayed himself as a wealthy jetsetter, driving around Beverly Hills in a buffed Rolls-Royce one day, partying with soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo on a private yacht in the United Arab Emirates the next. He favored the trappings of the hip-hop culture he’d aspired to since he was a boy: heavy diamond chains, Rolex watches, tailored blazers that showcased his considerable biceps. His shiny veneers and taut skin make it difficult to ascertain his age — public records list various birth dates, putting him somewhere in the range of 46 to 53.

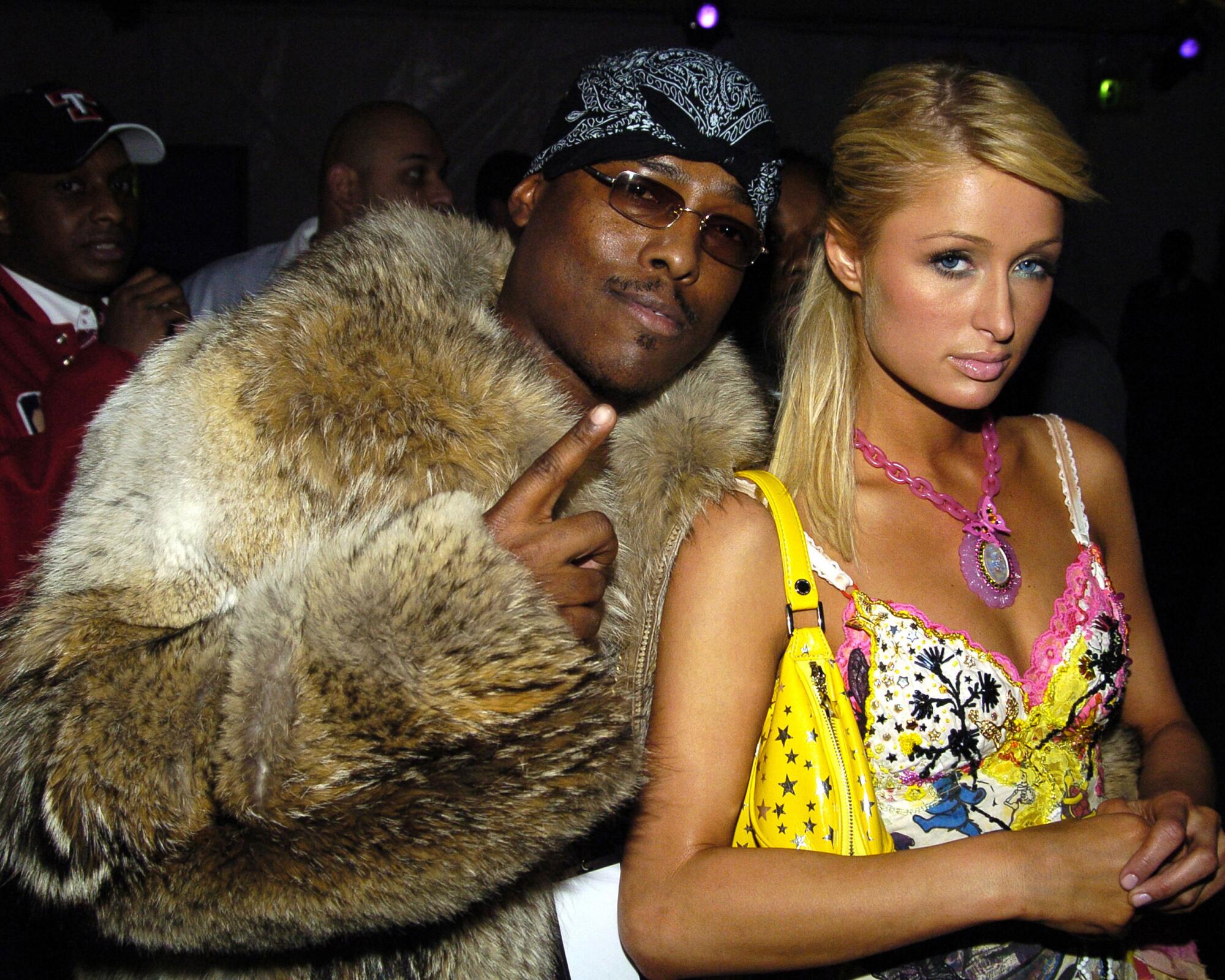

By the time he met Mosey, Bruny had spent decades honing his skills as a promoter. When he embarked on his career as a rapper in his 20s, he got Paris Hilton and Carmen Electra to appear in his music videos and turned up on “The Real Housewives of Orange County” to help one of its stars record her first song. He teamed with former L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca on a ballot initiative, promoting himself as a law enforcement-friendly rapper. For a time, he managed rappers Sean Kingston and Tyga. These were among the associations he boasted of in the promotional materials he shared with potential investors, collaborators and those Interscope executives to spotlight his accomplishments.

Won-G and Paris Hilton

(Getty Images / Jeff Kravitz via FilmMagic)

Mosey’s mother didn’t buy it. Though she had no evidence that Bruny was defrauding Mosey, Thatcher believed the manager was a negative influence. In 2023, she started doing more than just regularly checking the Instagram page where Bruny had 487,000 followers. When Google searches turned up references to lawsuits and scam alert websites, she hired a private investigator. The findings revealed numerous civil suits against Bruny alleging breach of contract, as well as a bankruptcy filing.

Thatcher shared the report with her son. But Mosey, just a few weeks out of his Interscope contract, continued working with Bruny, cutting ties with his old representatives and, according to Thatcher, distancing himself from her.

In October 2024, Thatcher died unexpectedly, of “a severe infection,” according to her obituary. She was 55.

“I just want my son away from [Bruny],” Thatcher said in an interview with The Times last summer. “I think he’s being controlled and manipulated by this guy who has convinced him that everyone in his life is against him, including his own family.”

A Times investigation found that, over the past two decades, Bruny has utilized a perception of affluence, supposed personal ties to celebrity and references to Haitian voodoo to convince more than two dozen people to give him thousands of dollars in investments or loans — money that they never saw again, according to lawsuits and bankruptcy filings. In the last 20 years, Bruny, or companies associated with him, have been sued at least 19 times in Los Angeles County Superior Court; in nine of those cases, he was ordered to pay judgments amounting to more than $2.1 million, none of which was ever paid.

During that period, he filed for bankruptcy three times in California, most recently in 2019, when between his personal and business Chapter 7 records he was discharged of roughly $9.9 million in debt liabilities.

Lawsuits and bankruptcy filings show a striking range of individuals who say they lost money through investments in Bruny’s music career and fashion line, including a septuagenarian Old Hollywood starlet, a cancer patient, a former girlfriend, an Australian fashion designer, an airline pilot and a UCLA professor who served on committees for Presidents Biden and Obama. Because the U.S. Bankruptcy Court found he had no legal obligation to pay his debts, none of them were ever repaid by Bruny.

Bruny did not respond to multiple requests for comment or a detailed list of questions sent to him by The Times via email and social media. His lawyer, Kenneth Sterling, said in a statement: “We find no merit to the allegations or implications currently circulating regarding Mr. Bruny. While, like many others, Mr. Bruny acknowledges he has grown from mistakes made in the distant past, these are nearly or more than a decade old and wholly irrelevant to his current work or character. It is worth noting that this current media inquiry appears to have been instigated by a former manager and relative of one of Mr. Bruny’s clients — individuals who, based on credible information, mismanaged and acted in their own financial interests at the expense of the artist.

“To be clear: Mr. Bruny has never been arrested, charged, or the subject of any criminal investigation. He has no criminal record. Any civil matters from years past have long been resolved and are, in every sense, ancient history. We live in a society that believes in growth, redemption, and new chapters — Mr. Bruny embodies all three.”

Mosey declined to be interviewed for this story, saying via text message that he had “nothing but great things to say about Won.” When asked specifically if he believed a former manager and relative mismanaged and acted in their own financial interests at his expense, Mosey did not respond.

Lil Mosey, now 23, was born Lathan Moses Stanley Echols; his father, Thatcher said, wasn’t very involved in his upbringing. He was 15 when his music started to take off online — he and his two brothers created a makeshift studio in a closet of their Washington state home, where Mosey made music that he then uploaded onto SoundCloud. In late 2017, his song “Pull Up” garnered attention on a rap blog. Music manager Josh Marshall reached out and flew the then-16-year-old and his mother to New York City. After discussions with about half a dozen companies, Mosey, represented by Marshall, signed with Interscope in March 2018. His debut album, “Northsbest,” was released that same year.

By 10th grade, Mosey had dropped out of high school and gone on tour with Juice WRLD and YBN Cordae. He told Billboard at the time that he was surprised by his sudden popularity. Asked how his mother was reacting to his newfound fame, Mosey told the magazine: “She always told me like, ‘Why do you want to do this? Why don’t you wait? You can always do this later. You could just be a normal kid.’ … But you can’t do it later. The time is now.”

Mosey’s sophomore album, “Certified Hitmaker,” took him to the next level. Featuring Chris Brown and Gunna, the 2019 release yielded the rapper’s first hit single: “Blueberry Faygo.” After the song went viral on TikTok, Mosey inked a $4-million deal with Universal Music Publishing Group in May 2020; to date, “Blueberry Faygo” has amassed 1.4 billion streams on Spotify.

His ascent to stardom came to an abrupt halt in April 2021, when the state of Washington charged Mosey with second-degree rape. An affidavit filed in Lewis County Superior Court alleged that, in January 2020, Mosey had sex at a house party with a young woman who was too intoxicated to consent.

Interscope did not terminate Mosey’s contract but put its work with the rapper on pause until a verdict was reached.

Tyga, left, and Won-G in 2019.

(Johnny Nunez / Getty Images)

According to Thatcher, it was during the two-year trial that Mosey’s relationship with Bruny deepened. He had met Bruny through Sean Kingston, then best known for the 2007 hit “Beautiful Girls.”

According to press clippings he posted on social media, Won-G Bruny was born in Port-Au Prince, Haiti, and immigrated to the U.S. when he was 13. Bruny’s father, MacNeal Bruny, has said he was a high-ranking member of the Haitian army during the authoritarian regime of Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier. After MacNeal noticed an advertisement for a company that would press compact discs for cheap, Bruny embarked on a music career, releasing his first independent rap album in 1995.

In 2001, he teamed up with an unlikely partner — Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of the president of Equatorial Guinea, who was attempting to become a rap mogul. Mangue released Bruny’s third album on his newly launched TNO Entertainment.

But that album was unsuccessful, and TNO never released any music of note. When Bruny filed for bankruptcy for the first time, in 2002, he owed TNO $75,000 relating to a recording contract.

Bruny forged ahead. In 2004, he landed his first record deal with a major label: Sanctuary Urban, an imprint headed by Beyoncé’s dad, Mathew Knowles. That year, Bruny also teamed up with L.A. County Sheriff Lee Baca to support a ballot initiative that proposed raising taxes to fund broader law enforcement. To help gather signatures for the initiative, Bruny said he planned to drive around the city with his “Haiti Boys Street Team” in 28 Ford Excursions with 27-inch wheels plastered with decals of him and Baca.

“Pictures belie personality,” Baca told the Los Angeles Daily News, which described Bruny as a “rapper with a $250,000 Elvis watch and penchant for fur coats and Rolls-Royces.” “He’s a faith-based hip-hop star. No vulgarity. No anti-public safety … There’s nothing in his work that’s bad boy.”

But Bruny had had at least one previous run-in with the law. In 1998, a judge in Pomona granted Bruny’s ex-girlfriend a one-year domestic violence restraining order. In court documents, the woman claimed that she and Bruny had been dating for two years and “during that time he demonstrated extreme physical violence by kicking, slapping, grabbing, bruising, spitting on my face and cutting my face.”

A year after his philanthropic efforts with the sheriff, Bruny began facing a string of lawsuits. There were four in 2005 alone, all alleging breach of contract. One case revolved around Bruny’s first role in a movie, an independent film called “Hack!” During production, the plaintiff — director Mike Wittlin — claimed that Bruny missed a day of shooting, leading the actor and the filmmaker to get into a heated verbal dispute. Following the argument, Bruny refused to return to set, according to the lawsuit. In his complaint, Wittlin said he then received an email from Bruny’s father, MacNeal, drafted “on behalf” of his son, which read: “I’m from a Royal family, little do you know. … I’m a self-made man and a self-made millionaire.”

When he was deposed in 2006, Bruny arrived wearing what Wittlin’s attorney described as a “large diamond ring” that Bruny said was owned by his father. “I just told you I don’t own anything,” Bruny said, according to the transcript. “I’m not a millionaire, I’m bankrupt.”

The court ultimately dismissed the case on the condition that Bruny pay $25,000 to the plaintiffs; according to a 2008 court judgment, he breached that settlement and was subsequently ordered to pay $108,236.25 in damages and fees. Wittlin told The Times he never received any of the money.

A clean-cut, God-fearing rapper. That was how Bruny represented himself to a pair of friends in their 70s.

Gita Hall, then 71, and Terry Moore, then 75, met for lunch nearly every day at Caffe Roma in 2004. They’d reminisce about the golden era of Hollywood: Hall, a onetime Miss Stockholm, had been photographed by Richard Avedon as a Revlon model and appeared in films like 1958’s “The Gun Runners”; Moore earned an Oscar nomination for her turn in 1952’s “Come Back, Little Sheba,” had a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and dated Howard Hughes.

Grant Cramer, Moore’s son and a film producer, had an office a block away from his mother’s favorite restaurant in Beverly Hills. One day, she wandered in unannounced with Hall and about 10 Haitian men he’d never met.

“They all sat down and said, ‘We are hereby announcing that we are becoming hip-hop moguls,’” said Cramer. “‘We’re going to raise all this money and become his producers.’”

He was stunned. He was fairly certain the women had never heard a hip-hop song before. After Bruny and his entourage left the office, Cramer tried desperately to talk them out of their new plan.

“But they were dead set on it,” said Cramer. “I said, ‘You’re going to lose your money. You don’t know who these guys are.’ And they said, ‘Oh, yes, we do. They’re Christian.’ Bruny had shown them this video he made with Paris Hilton, told them it was the new hottest thing, that he needed money to release a new album and they were gonna make 10 times their money.’”

(Through her publicist, Hilton did not respond to a request for comment.)

Hall had just moved back to Los Angeles after decades in Manhattan following the death of her husband. She wasn’t wealthy but had enough money to sustain her lifestyle, said one of her daughters, Tracie May Wagner.

Wagner joined Hall and Bruny for dinner at Mr. Chow one evening in an attempt to suss out her mother’s unlikely new friend.

“He rolls in, in his Rolls-Royce, handshake handshake, I know everybody on the planet,” remembered Wagner, a former entertainment publicist who now lives in Vietnam. “On first impression, he was very kind and sweet and doting. He would open the door for you. He would pull out my mother’s chair. He’d have this look in his eye of adoration, like, ‘I’m such a fan of yours. I know you were such a movie star.’ He would just keep playing into her reliving her golden years in her heyday.”

Hall ultimately loaned Bruny $93,000 under a contract that promised she’d be repaid in six months. But the day she and Moore transferred their money to Bruny, “Won-G and the money disappeared,” Cramer said.

“No album, no nothing,” said Cramer, who did not know the sum Moore invested. “Money’s gone.”

Hall sued Bruny, making similar allegations. In 2007, a judge ordered the rapper to pay her $107,319.45 — a sum her attorney said the family was unlikely to ever collect.

“When it was time to seize assets, he had none,” said Hall’s daughter, Wagner. “The mansion in Beverly Hills, all the cars, the jewelry — it was all registered under someone else’s name.”

That same year, Bruny appeared on two episodes of the Orange County installment of Bravo’s “Real Housewives” franchise. In Season 2, cast member Jo De La Rosa decided she wanted to be a singer. She invited Bruny and another producer to her home to discuss the possibility of collaborating.

“Won-G is a rap artist, producer, super-talented, amazing person,” De La Rosa said in a voice-over as Bruny exited a white Rolls-Royce in her driveway. “He’s worked with some big names in the music industry.”

De La Rosa recorded a song with Bruny but soon abandoned her musical pursuits. Bruny also shifted in another direction, attempting to expand his brand from music to fashion.

Taking a page from wealthy rappers like Jay-Z, 50 Cent and Sean “Diddy” Combs, he created an extensive pitch deck for investors, explaining how he’d use his music career to leverage “ancillary revenue possibilities” with a clothing line called Sovage. His business documents said he had signed Philippe Naouri, one of the designers behind Antik Denim, to create his jeans. (Naouri did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Bruny’s deck also included collages of him with dozens of celebrities — Kanye West, Bill Maher, Fergie — as well as images of him taken by paparazzi. His pitch said his forthcoming album would feature “exciting collaborations” with artists like Snoop Dogg, Alicia Keys and Timbaland, none of which ever came to fruition.

In 2001, Garry Heath, a technology executive, loaned Bruny $170,000. When he reached out to Bruny for repayment, Heath said the rapper warned him to stop “harassing” him because his father was “connected in Haiti. My family could really do damage to you if you don’t watch out.” One day, Heath said, Bruny’s father and brother turned up at his home in Orange County trying “to bury some voodoo thing in my yard that was gonna ‘protect me’ from losing my money or something … they wanted me to pay them, or else it was going to turn into a curse.”

In 2016, Heath finally decided to take Bruny to court. After a process server was unable to track him down to deliver legal documents for nearly two years, Heath said, a judge ultimately decided that posting the lawsuit on Bruny’s active Facebook page constituted service.

Bruny evaded service and court proceedings so many times that at least seven plaintiffs, including Heath, received default judgments in their favor in advance of any trials.

When she was fighting to recoup her late mother’s money, Wagner often relied on her connections with colleagues in the publicity industry to find out what events Bruny might attend. Then she’d show up to confront him. But after a few years without any movement in court, she backed off. “I knew it was never going to amount to anything, and I started having fear,” she said.

In December 2019, Bruny filed for personal bankruptcy and non-individual bankruptcy on behalf of his company, Real Sovage, claiming $9.9 million in debt liabilities. In his bankruptcy documents, Bruny said his personal assets amounted to just $10,700, about half of which consisted of “real & costume jewelry.”

“Debtor is currently living with friends until he is back up on his feet,” said the paperwork. “He hopes to be able to move into his own home within the next 6 months.”

On Instagram, Bruny had been depicting a very different image. Earlier that year, he posted a photo featuring himself, the rapper Tyga (his first major management client) and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. “I’m so happy to be your friend and to study and learn your method to success,” the caption of the February 2019 photo read. (A source close to Bezos said the billionaire doesn’t know Bruny and has never interacted with him beyond posing for the photograph.)

“He had the audacity to come to court in a T-shirt and flip-flops, looking like he was in poverty just a few days after posting pictures of himself driving a Rolls-Royce car and wearing a Rolex watch.”

— Garry Heath, a creditor who faced Won-G Bruny in bankruptcy court

In October, Bruny’s dad shared an image on Facebook of a Mercedes-Benz G-Wagon — which retails for over $100,000 — describing it as “A VERY EXPENSIVE & PRECIOUS GIFT FROM WON-G AND HIS PARTNER TO SHOW ME THEIR APPRECIATION”.

Angered by the lifestyle he saw online, Heath — whom Bruny had yet to pay a $229,984 judgment — unsuccessfully attempted to get his money back in court.

“He had the audacity to come to court in a T-shirt and flip-flops, looking like he was in poverty just a few days after posting pictures of himself driving a Rolls-Royce car and wearing a Rolex watch,” said Heath, who presented images from Bruny’s Instagram page to the court. “He said the car was borrowed from a friend and the gold chains and watch were fakes.”

After a bankruptcy is filed, creditors can meet a trustee to ask questions about the finances of the debtor. In California, creditors then have 60 days to file a complaint like Heath did, objecting to the discharging of a specific debt. It is unclear if any of the 25 other creditors listed in Bruny’s personal filing took this step — but legal experts say such paperwork often falls through the cracks.

“Bankruptcy is premised on all the creditors receiving notice of the bankruptcy case and either taking action or not. But people don’t read their mail,” said Evan Borges, the attorney who represented “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika Girardi in the bankruptcy proceedings against her estranged husband, disbarred lawyer Tom Girardi. “It’s a hard-and-fast deadline to file a complaint, and if people miss it, they’re screwed.”

Without such complaints, it falls on the trustee appointed by the Justice Department to monitor Chapter 7 cases for potential fraud. “But they drop the ball all the time,” said Borges. “They’re there as watchdogs to safeguard the integrity of the system, and they’re supposed to refer people who have abused the bankruptcy system to the United States attorney for criminal prosecution. But they’re extremely overworked and can barely keep up.”

Even as he filed bankruptcy, Bruny was entering a business relationship with Tyga, a Grammy-nominated artist whose hit “Rack City” was then quadruple platinum. In his subsequent press materials, Bruny took credit for orchestrating “a huge comeback” for Tyga, whose music had become less popular than his relationship with Kylie Jenner.

But Bruny and Tyga parted acrimoniously. In April 2022, Bruny sued Tyga, alleging breach of contract and promissory fraud, saying he was owed $800,000 for his work on behalf of the rapper. A few months later, Bruny’s lawyer requested the case be dismissed. (Tyga did not respond to a request for comment sent to his publicist.)

By then, Bruny had moved on with Kingston, another partnership that would crash and burn.

“He promised us the world. He promised my son, ‘If you sign the papers, I have a $3-million deal,’” Janice Turner, Kingston’s mother, said in an interview.

During the year Kingston and Bruny worked together, Turner said, Bruny received 20% of everything Kingston made off his prior hits, but they were not satisfied with the partnership. Turner said she kicked Bruny out of the house he was sharing with her and Kingston and fired him. “I told him, ‘You’re a failed artist trying to live through other people,’” she said. “He was upset with me. He said that’s why God doesn’t like me.”

(In March, in a case unrelated to Bruny, a Florida jury found Turner and Kingston guilty of wire fraud for failing to pay for more than $1 million in luxury goods. Turner and Kingston await sentencing in July.)

As Bruny’s relationship with Kingston soured, he was strengthening his bond with Lil Mosey.

They began sharing a Redondo Beach rental — “I have a mansion in Beverly Hills, but it’s cooler here for the summer,” Bruny claimed, according to Mosey’s mom Thatcher. By the fall, Bruny had floated his first business proposition to Mosey: investing $50,000 in a four-unit apartment building being built by a company called Harmony Real Estate Developments.

“See when Justin [Bieber] gave Scooter [Braun] his trust they went to billions,” Bruny texted Mosey in February 2023, when he sent through more details about the project. “This is how I want to be for you as being seen together as business partners will take us to a whole new level.”

But Mosey’s team advised him against pursuing the opportunity. His funds were dwindling as he continued to fight the rape charge. As a jury prepared to deliver its verdict, Bruny urged Mosey to partake in a rum-bath ritual, according to two sources close to the situation. In the voodoo religion, rum baths are used “for good luck or to take off something bad,” said Elizabeth McAlister, a Wesleyan University professor whose research centers on Afro-Carribbean religions like Haitian voodoo.

On March 2, 2023, Mosey was acquitted.

“It’s been tough, mentally,” the rapper admitted to Billboard in an interview a month later. “It sucks to have something like that be attached to my name, knowing I didn’t do it, and the whole world can see that. … I feel like my last two years kind of been a sickness.”

While facing bills from the trial and the interruption of his music career, Mosey’s bank account had dwindled from millions down to a couple hundred thousand dollars — and he owed more than that in legal bills, according to a former business associate who requested anonymity because he still works in the music industry. Mosey’s team worked out a payment plan with Mosey’s attorney and jumped into action, setting up a nationwide college tour to bring in immediate revenue.

But Mosey wasn’t interested in doing the shows.

“Suddenly this tour that had been put in place wasn’t enough money, and he kept saying he deserved more,” his mother said.

Then Mosey began requesting his financial documents from his accounting team — materials he had never before asked to view. The team obliged. Gathering nearly 70,000 pages of bank statements, royalty metrics and tax returns, members of Mosey’s team, his mother and Marshall, met in L.A.

At the Glendale rental where Mosey was staying, Thatcher said, the team presented a new business strategy, suggesting new profit avenues like a beverage company or a lifestyle brand. But Mosey felt like he was being ambushed, his mother said.

Before she left, Thatcher made a final plea: “Please promise me you won’t sign a contract with Won-G,” she said. “Think about it. Talk to other people. You don’t have to sign a contract with him yet.”

Thatcher did not manage her son’s career, though she was a signer on his bank account when he was a minor. In recent years, he sent her around $4,000 a month to cover her rent in Washington, according to Mosey’s former business associate. Sometimes, Thatcher said, she would offer Mosey financial advice — “I think you’re spending too much. I know it feels like a lot of money right now, but this is not gonna last you forever” — but he disregarded it. She was also wary of becoming “that mom that took money from my son,” so she kept her job in the education sector.

Before her death, she’d started work on a trilogy of children’s books with an L.A.-based husband-and-wife writing team, Maya Sloan and Thomas Warming. The couple became some of the only people she confided to about Mosey.

“I felt terrible for Angela, because I saw her desperation and anguish when she’d come to L.A. in the hopes of just having a brief moment with her son,” said Warming. “She would keep motel rooms and wait for him to call or sit in cars outside his house to try to talk to him. That’s how difficult it had become.”

Sloan began helping Thatcher research Bruny and connected her with a private investigator. When the PI report confirmed Thatcher’s fears, she pressed Mosey for an in-person meeting. According to Thatcher, Mosey went home and read through the background documents. A half an hour later, he called, saying “I don’t know what to do. I’m really confused.’”

“I said, ‘Well, I know you’ve signed a contract with him. But if you really want, there’s always a way out. And I’m here for you,’” Thatcher said.

That night, he left the home he shared with Bruny and stayed in a hotel. Still uneasy, he flew back to Seattle to visit his family in Washington. But by the end of the trip, any concerns he’d had about Bruny had seemingly vanished. He returned to L.A., and they continued working together.

Mosey had given his mother something that would provide her with insight into his relationship with Bruny: His old phone, which was still logged into Mosey’s account. She had access to his text messages.

She began scrolling through her son’s interactions with Bruny. In August 2023, she saw herself mentioned: Mosey was urging him to stop mentioning voodoo in conversation with his mother.

“you gotta stop saying your the reason i beat the case bro cuz even if ogu is the reason i beat it anybody that does not know what voodoo is will not believe you and it makes you look bad for trying to take credit,” Mosey said in a text message. “not saying that you and ogu did not help i’m just saying it makes you look bad cuz most people will not believe you.”

But in the days that followed, Bruny mentioned Ogu, a warrior god, numerous times as the battle with Interscope ramped up.

“papa ogu never loses or fails. … I have won battles taken Artist out of many situations that are legal contractual,” Bruny texted his client. “You have to be a killer, I’m like trump. … You have 24 hours to give me a answer or I will drop a bomb on you.”

“my Power is ordained by God, No one will understand the angels that walk with me … My father & Ogu walk with us, interscope are fools”

— A 2023 text from Bruny to Mosey

After Bruny sent his Aug. 22 email to Interscope executives demanding Mosey be let out of his contract, text messages revealed he continued to press other members of the rapper’s team. Two days later, he messaged Marshall, Mosey’s prior manager, demanding him to aid in the situation with the record label.

“I now have everybody’s home address and will pop up to their home at 1 AM in the morning and start waking them up by knocking on your door,” Bruny wrote to Marshall in a text reviewed by The Times. “We are very smart it is not a threat. It is not a violent act in America. You’re allowed to walk up to anybody you want and have a discussion with them.” (Marshall did not respond to interview requests for this story.)

In the end, Interscope agreed to let Mosey out of his contract with the stipulation that the company would continue to collect around 2% of his future earnings, according to the former business associate.

“my Power is ordained by God, No one will understand the angels that walk with me,” Bruny texted Mosey after the deal was executed. “My father & Ogu walk with us, interscope are fools … What interscope feared happened., you finding me was the blow. God, Ogu destroyed all of them, including that lying bitch in court.”

Thatcher was so worried about her son that she consulted Rick Ross, a cult intervention specialist whom she and Sloan had seen pop up in a few true crime documentaries. While she considered hiring Ross, she continued to strategize with Sloan. Last August, they approached the FBI about Bruny, then met with the director of the Bureau of Fraud & Corruption Prosecutions in the Los Angeles district attorney’s office.

A source close to the D.A.’s office confirmed a meeting with Thatcher and Sloan took place but said no investigation into Bruny was pending. Laura Eimiller, the FBI’s media coordinator, said the bureau does not confirm or deny information provided to the organization unless it results in a court charge.

Two months later, Thatcher died.

Sloan, who spoke to her the night before her death, said she was slurring her words because her “tongue wasn’t working right.” Thatcher told her friend that a doctor told her she’d be OK and that she just needed to take the antibiotics she’d been prescribed.

“Her spirit was broken,” Sloan said. “She was afraid that her son was … going to lose everything he’d worked so hard for. That he wasn’t going to ever be able to do a real album again.”

In February 2024, Mosey officially went independent, signing a global distribution partnership with Cinq Music. “As a manager, it is rare to have a young artist that is truly gifted in creating hit records and is equally an amazing human being,” Bruny said in the press release announcing the news. Since then, Lil Mosey has released an EP and a few singles but none have brought him close to the commercial success of “Blueberry Faygo.” This summer, he has 10 North American concert dates lined up at venues that can hold between 450 and 1,500 people; tickets start at $31.

In one of Mosey’s recent Instagram posts, he starts out standing in front of a Rolls-Royce on that palm-tree-lined street in Beverly Hills that all influencers flock to. The April photo shoot continues: He’s flipping the bird. He’s holding a huge bag from Louis Vuitton.

But scroll down just three posts, and the tone shifts. He’s on the ground, seated next to a pay phone. “miss u mom this one’s for u,” say the words below the picture. It’s from November 2024 — just weeks after his mother’s passing — an announcement for his new single, “Call.” He wrote the song for Thatcher, its lyrics lamenting how he’d “give everything” to hear her voice again. Between his rap verses, there’s an interlude where he samples voicemail messages he’s saved from her.

“Hey, it’s me, your mom,” she says gently, barely audible. “Just checking in, hope everything’s good. Stay safe, be strong, love you. You know I’m here for you, always. Reach out anytime. ”

Times librarian Cary Schneider contributed to this report.