When USC trustees selected Carol Folt as their next president, they gave her one of the most challenging mandates in American higher education: Restore trust in a university diminished by scandals.

She replaced key administrators, brokered a $1-billion settlement with alumnae victimized by a sexually abusive gynecologist, hired a new football coach and authorized the removal of the name of an antisemitic, eugenics-supporting former USC president from an iconic campus building. To dozens of Japanese American ex-students unjustly incarcerated during World War II, then later denied reentry to the university, Folt awarded honorary degrees.

“We are bringing some closure and perhaps healing,” Folt told descendants of those former students at a 2022 gala for Asian American alumni, distilling two key themes of her five-year tenure.

But a cascade of decisions that Folt made this spring around USC’s commencement and Israel-Hamas war-related protests have inflamed tensions and opened fresh wounds, presenting the most significant test of her tenure as university presidents around the country wrestle with similar dilemmas.

Asna Tabassum, a graduating senior at USC, was selected as valedictorian and offered a traditional slot to speak at the 2024 graduation. After on-and-off campus groups criticized the decision and the university said it received threats, it pulled her from the graduation speakers schedule. Ultimately, the main commencement ceremony was canceled altogether. Tabassum was photographed on the USC campus on April 16.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Citing unspecified safety threats, Folt rescinded pro-Palestinian valedictorian Asna Tabassum’s speaking slot in USC’s main commencement ceremony. Days later, amid a swell of outrage, Folt “released” director Jon M. Chu and other celebrities from receiving honorary degrees at the ceremony.

After students set up a tent encampment in support of Palestinians and demanded that USC divest from financial ties with Israel, Folt and her team called in the LAPD, and 93 were arrested. Last week, Folt canceled the “main stage” commencement ceremony altogether, depriving students and their families of a treasured ritual.

For nearly two weeks, Folt made no public remarks, and her silence fed a growing sense that the university’s top executive was missing in action, according to interviews with faculty, students and alumni.

In balancing campus safety and the right to protest with concerns about antisemitism and anti-Muslim hatred, Folt was bound to take criticism from all directions.

But many saw the damage at USC as self-inflicted.

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators do yoga at a sit-in at USC on April 24.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Tabassum was not known to be a campus activist, and canceling her speech in the name of safety was seen by some as shutting down a Muslim student’s voice at the very time the world needed to hear it. “Let Asna speak” became a rallying cry at USC and beyond.

“This is an epic failure in leadership,” said Annette Ricchiazzi, a USC alumna whose daughter graduates this month. Ricchiazzi, a former USC administrator who now works as a consultant for nonprofits, predicted that the events of April would end up as a case study taught to crisis communications or business classes. “I don’t think she’s a great decision-maker,” she said of Folt.

Folt is now heading into a third week of tumult, with no end in sight. Dozens of faculty have joined the call for her to step down, and more than 350 have called for a no-confidence vote. Students gathered Monday outside the university-owned mansion in Santa Monica where the president lives, chanting: “Carol, Carol, you can’t hide.” Some faculty members staged a campus march on Wednesday in support of students.

In an interview with The Times on Monday — her first extensive remarks since the crisis began — Folt said she “absolutely” would not resign and forcefully defended her administration. Asked if she had any regrets, she said, “I believe that all along the way, we’ve made the right choice.”

“For me, I have a very clear North Star: that I am the person at the university, no matter how complicated the issue and how much I empathize with everybody involved — which has been true for me — I still in the end have to sit back and say, ‘What can I do to keep my campus and my people as safe as possible?’”

Folt highlighted the current moment as “a very volatile time. Not just at USC.” She framed division and discord as warranting a safety-above-all-else approach: “When these tensions and these kinds of confrontations … arise, you have to be even more vigilant because the unexpected, sadly, can take place.”

That philosophy was derided by critics as cautious to an extreme — until violence broke out at UCLA Tuesday night, with counterprotesters attacking and bloodying those at a pro-Palestinian encampment. UCLA administrators, who had adopted a more hands-off approach while Folt took heat for arrests at USC, are now being lambasted for allowing violence to escalate. Early Thursday, police dismantled the UCLA encampment and arrested more than 200 people.

Folt was at her most defensive, and, at times, contradictory, when explaining why and how her team had communicated its decisions.

Asked why nearly two weeks passed before she addressed students, faculty, parents and alumni, Folt countered, “I have been talking to people all the time,” suggesting that small meetings were the same as public comments to a university of 4,800 full-time faculty, 48,000 students, and alumni numbering a half-million.

Still, Folt acknowledged that she needed to take on a more public profile and “maybe be a little bit better at explaining to people.”

Folt’s interview came on the heels of a 90-minute meeting on Monday with four students representing an encampment of pro-Palestinian protesters that remained on campus. No resolutions were reached.

Los Angeles police officers face off with students protesting against the Israel-Hamas war at USC on April 24.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

“What was more important is that we tried to talk,” Folt said.

After a second meeting Tuesday, Folt posted on X that students “seemed more interested in having me issue a political statement in support of their viewpoint as opposed to coming up with practical solutions to resolve the situation.”

Jody Armour, a law-school professor who accompanied the protesters in meeting Folt, said students were firm in their requests that USC boycott and divest from ties with Israel. Folt, he said, was “gracious,” but he felt a nagging sense that the acrimony and tension on campus, along with Folt’s summoning of the LAPD, could have been avoided.

“If she had walked over [to demonstrators] … and said, ‘Let’s have a conversation. What’s going on? Can we find some common ground?’ it could have made a world of difference,” Armour said.

Instead, he said, “She took an adversarial and militaristic posture toward these students who were doing what we teach them to do: think critically, oppose injustice and stand for themselves.”

In a USC Academic Senate meeting on Wednesday with faculty, Folt conceded that she should have reached out to protesters earlier.

“I regret that. Humanity would have been better served for me if I had gone out there,” she said.

Underscoring the challenges Folt faces, her meeting with the protesters drew condemnation from pro-Israel Jewish students like Sabrina Jahan.

Public safety officers confront pro-Palestinian demonstrators at USC on April 24.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

“I was proud of her and leadership last week when they called the LAPD to campus to arrest people who were violating the law and student handbook,” said Jahan, a 22-year-old senior majoring in business administration.

“Not anymore,” she said, accusing protesters of “using antisemitic slogans.”

Versions of that debate played out in a 9,000-member Facebook group for USC parents. Some applauded Folt; others found her shifting “blame to everyone else.”

For a contingent of the USC community, Folt and the university’s primary error was failing to fully scrutinize Tabassum before naming her valedictorian out of nearly 100 applicants with GPAs of 3.98 or above.

A biomedical engineering major who is Muslim and wears a hijab, Tabassum included a link to a pro-Palestinian website on her private Instagram profile. That site states that “Zionism is a racist settler-colonialist ideology” and calls for “the complete abolishment of the state of Israel” so that “Arabs and Jews can live together.”

Lloyd Greif, a USC alumnus and prominent donor who is the son of Holocaust survivors, said it was “mind-boggling” that university leaders would choose a valedictorian who posted an online link to views that many Jewish people find abhorrent.

“They have a field of 100 eligible candidates, and they select this one without properly vetting them for whether they had antisemitic views?” Greif said. “Just come clean and say, ‘We screwed up.’”

In an interview last month, Tabassum insisted she is not antisemitic and said she was planning to convey a message of hope in her commencement speech.

“It was shocking to see [Tabassum] painted as some wild-eyed radical based on some link in her bio,” said Ariela Gross, who taught at USC’s law school for nearly three decades before joining the UCLA faculty last summer. “Safety concern was just a fig leaf for canceling what they feared would be an exercise of free speech.”

Folt said she had lauded Tabassum at an academic convocation dinner on April 4.

Asna Tabassum, facing, a graduating senior at USC, receives a hug of support from a friend on the USC campus on April 16. Tabassum was selected as valedictorian and offered a traditional slot to speak at the 2024 graduation. After on-and-off campus groups criticized the decision and the university said it received threats, it pulled her from the graduation speakers schedule.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

“It was quite a lovely event,” Folt recalled. “But the volume, the feedback, what was happening online, the nature, the tenor, the tone, was so extreme. Our threat assessment [team] became very, very concerned.”

USC has declined to detail the threats, and local and federal law enforcement officials told The Times that they had not been notified by the university of anything specific.

Pressed on what elicited the safety concerns, Folt acknowledged, “I did not read all of those threats.”

“I think they were all coming in from all different sorts of directions. It wasn’t just a single thing,” she said. “And I know that this action broke trust with many members of my community, and of course that really saddens me, and I feel very determined to continue to try to build that trust.”

Advocates on all sides criticized Folt for invoking “safety” as a justification, though they differed on their reasons.

By refusing to specify the safety threats, Greif said, USC administrators had maligned the Jewish community.

“This effectively put a bull’s-eye on the back of every Jewish student on campus,” he said.

Armour, an expert in tort law, said the idea that safety was the sole criterion was exasperating and glib.

“If safety was the only thing that mattered, then no one would ever get behind the wheel of a car,” he said. “We shouldn’t prioritize safety over other important values, even if it involves hearing things that make people uncomfortable.”

A marine and environmental biologist who received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UC Santa Barbara and a doctorate from UC Davis, Folt, 73, has worked in university administration for decades. She was provost and interim president at Dartmouth before heading south in 2013 to become chancellor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Petite and energetic, the Ohio-born Folt brought a Midwestern warmth to her dealings with students, posing for selfies and cheering on UNC sports teams.

Protesters chant while opening a banner for a short period at the beginning of a speech by Carol Folt during her inauguration as USC’s 12th president on Sept. 20, 2019.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Her final years there were marred by fierce conflict around a campus monument of a Confederate soldier known as Silent Sam. Folt was criticized as ineffective for not removing a symbol of racism; she said she was hamstrung by a state law that barred her from doing so.

After protesters tore down Silent Sam in 2018, leaving behind a pedestal and plaque, the racially charged debate over its fate intensified. At one point, university leaders proposed a visitors center where it would be displayed in context. In January 2019, Folt stunned Chapel Hill: she announced her resignation and on the same day ordered the removal of the rest of the monument.

She offered a rationale that echoes at USC today.

“The presence of the remaining parts of the monument on campus poses a continuing threat both to the personal safety and well-being of our community,” Folt said at the time. “No one learns at their best when they feel unsafe.”

By then, USC had launched its search for a new president, and Folt had been in contact with billionaire developer Rick Caruso, then the chair of USC’s governing board. Folt called Caruso and told him about her plan for Silent Sam in advance, even offering to withdraw from consideration.

If anything, Folt’s move boosted her chances at running USC. Caruso said in 2019 that he found Folt “incredibly brave” and told her, “I love you more today than I did yesterday.”

At USC, Folt’s annual compensation package has exceeded $3.8 million, of which $2.3 million is her base salary and bonus, according to the university’s most recent nonprofit tax return.

Within a year of Folt taking over as president, the pandemic threw operations into upheaval. Calls for racial justice in the summer of 2020 roiled USC and nearly every other educational institution. Folt renounced “anti-Black and systemic racism.”

That summer also saw a campaign to impeach USC’s student body vice president, Rose Ritch, a Jewish student who identified as a Zionist.

The grounds for impeachment did not list Ritch’s Jewish or Zionist identity, but an online campaign elicited a flood of antisemitic comments and messages on her Instagram page.

The day after Ritch resigned in the summer of 2020, Folt issued a campus-wide letter lamenting the student’s mistreatment and asserting that “anti-Semitism in all of its forms is a profound betrayal of our principles and has no place at the university.”

Some students, faculty and outside groups were angered by Folt’s letter, which they saw as inaccurately fusing antisemitism with anti-Zionism.

Four years later, a civil rights probe by the U.S. Department of Education is ongoing; Ritch alleges that USC failed to protect her from harassment on social media. After news of the federal probe was disclosed in 2022, Folt touted USC’s efforts at combating anti-Jewish hatred.

Greif, the alum and donor, called the last month at USC “Rose Ritch on steroids.”

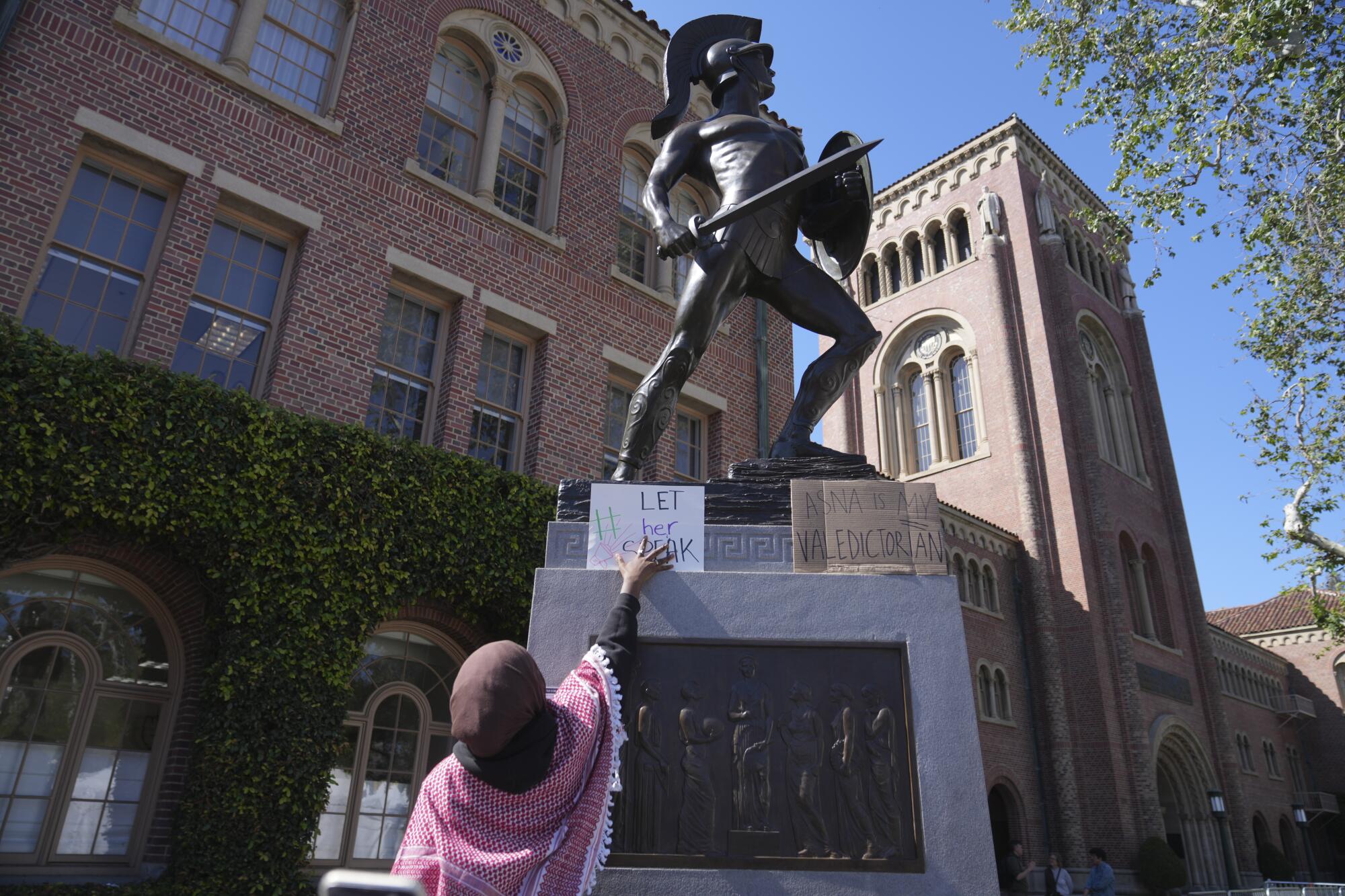

A Pro-Palestinian student places a sign on the Tommy Trojan statue on the USC campus on April 18 during a protest against the cancellation of valedictorian Asna Tabassum’s commencement speech.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

“There’s no question that Jewish students are scared and not feeling safe,” Greif said. He pointed to vandalism on campus — like writing “say no to genocide” on the Tommy Trojan statue — as contributing to a hostile environment. On Tuesday, USC found a swastika scrawled on a post outside campus and swiftly removed it.

One of the few speaking out in support of Folt has been Caruso, who told TMZ that she was doing “an incredible job in managing through a tough situation.”

TMZ host Charles Latibeaudiere pressed Caruso on the line between free and hate speech, like chants of “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” Jews see the phrase as a call for the destruction of Israel, while pro-Palestinians — including Jewish students who have chanted it on campuses — see it as a cry for freedom.

Caruso, a lawyer, said the line wasn’t difficult to identify.

“The minute that the recipient feels bullied, feels threatened, feels unsafe, I believe it crosses that line,” Caruso said.

Faculty and free-speech advocates, however, see that standard as nebulous — the type of reasoning that could be deployed to justify censorship of nearly any controversial viewpoint.

Protesters are detained by LAPD officers who were trying to clear the USC campus during a demonstration against the war in Gaza.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles)

Folt told The Times that “From the river to the sea” and other common pro-Palestinian statements “clearly … are antisemitic words to many people.”

With a pro-Palestinian encampment of at least 50 students and faculty still on campus as of Thursday afternoon, Folt said she did not “have any intention” to call the LAPD to crack down in the future but balked at promising not to do so.

Folt also declined to say whether USC would ask for charges to be dropped against those arrested last week, 53 of whom were students.

“My intent is this: To try to come to a resolution that is peaceful. We tend to be very understanding when we have disciplinary actions, and we won’t rush it,” she said. “But we have a lot of students that want to graduate, and I fully expect them to be able to go through that.”